This is a free post so feel free to share it! Also please be kind about any errors as I’m still in benzo withdrawal after involuntary hold incident after Easter Sunday… but if Jordan Peterson can make it then so can I…

A while ago, I came across an extraordinary little book in the Oxfam on St Giles’, no doubt cast out with the rest of the Benet’s library (I’m so sad I never got to visit) by Dom Sebastian Moore entitled The Fire and the Rose are One. I can’t remember too much of it and I don’t have it to hand but I do remember a passage which made a profound impression on me and changed my faith. He argues that the original sin is not fear but guilt. I can’t remember why But I remember a haunting meditation he gives of the early Christians having witnessed the resurrection. They had lived their whole lives believing that death was real. They had seen something, they had seen Lazarus, but this could be a fluke, a medical marvel. We see these every day and don’t cease to believe in death. But Christ rose. He appeared to the women, the was the grardener at the feet of the weeping Magdalene, he offered his wounds to Thomas, he broke bread at Emmaus. None of these post-resurrection appearances have anything resembling ordinary narrative equality. The original ending of Mark’s Gospel comes closest:

‘So they went out quickly and fled from the tomb, for they trembled and were amazed. And they said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.’

The beginning of the Easter Vigil At Friari…

Back in Oxford, acquired the book. Dom Sebastian says that ‘the real source of the human being’s absorbtion with himself, of his endless fascination with himself and of his passionate pursuit of meaningful survival is that he does not know where he comes from or whither he is bound.’ He goes on to ask if the only serious religious question today is ‘is all human self-awareness, when it finds its fulfilment in love, resonating, albeit faintly, with an origin that ‘behaves’, infinitely and all-constitutingly, as love behaves.’

it is like this / in death’s other kingdom / walking alone / at the hour when were are / trembling with tenderness, lips that would kiss / from prayers to broken stone

This leads to a conclusion that Dante’s looking at Beatrice is the paradigm for Dante’s looking at God.

‘There is an erotic dependence of the human being on the ultimate constitutive mystery that is pre-religious, universal, in the radical sense conscious, and shaping all life and culture.’

‘The spiritual vacuum of our time is due to the collapse of these gods. This diagnosis becomes clear once we understand that the hunger for God’s approval is built right into the human heart and cannot be got rid of.’ In a previous post I wrote about Paul Tournier’s diagnosis of modernity as a ‘neurosis of defiance.’ Dom Sebastian similarly argues that the there is an analogy in intellectual culture which leaves ‘people divided between the paramount private importance of the need to be in love and their public world which does not recognise this importance.’ None of our great philosophies are centred on love. Perhaps this is why people go chasing down the empty mines of phenomenology.

So we have a gap between what we are ontologically called to be and what our culture tells us to value. ‘What the gospel is about: love / what everyone is after: love / What our culture says about us: not centred in love.’ Dom Sebastian makes the point — see my last post, again! — that in such a culture whhere to the isolated self the minister speaks of self-actualisation. ‘To privatise is to keep private what starts private and desires to be public: in this case my and everybody’s felt need to be desired by one we desire.’ Christianity can be retooled as feel-good meditation.

Dom Sebastian has a lot of interest to say about love, power, and guilt. It reminds me, naturally, of Gillian Rose. He writes that ‘sexual passion is a bridge between power and love. It raises people above themselves to be powerful to change each other as the cause of desire. This power can change to tenderness, and vice versa. Therefore people sometime people take a bewildering plunge from extreme sexual tenderness to the infliction of sometimes very devious sexual manipulation. Sadomasochism is the contemporary sexual form of Hegel’s Master-Slave parable. Power is the enormously variegated link between anarchy and love. It is the manifestness of people in their value to each other, short of the full flowering of that mutual manifestness in love.’

What is the shadow of this inbuilt desire to love and be loved? It is guilt. ‘Guilt is the failure of love… In guilt I am “not functioning properly” as a person-for-persons. This is the radical guilt: unhappy unlove.’

‘I did him a bad turn years ago and I’ve had a grudge against him ever since.’

— Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

Maybe the disciples fled because they were afraid of something they couldn’t understand. But their primary sin was guilt. They couldn’t be there for Christ. They couldn’t return His love, even though it was the purpose they were created for, baked into their fast-beating hearts. Imagine the anguish of those disciples who fled the cross. Imagine Peter’s soul-crushing betrayal. Imagine His Lord’s eyes looking over to him after that. Not just a failure of love. A failure of the whole purpose of the world. But then that’s how God made us: knowing we were made for failure—and knowing, contra Calvin—that each of us could be pulled out of it and made right.

Dom Sebastian Moore points out how little psychoanalytic and psychological literature has been given to the experiences of these who were with Christ in his ministry, death, and resurrection. Even all those who knew of them, or knew of those of knew him. What would it mean fore death to come to an end? And for it not to be horrible, annihilation, but for it to be glorious, for it to be Him?

Sin—he reference Simone Weil—makes us recoil from others in pain. Love heals the repulsion. The only way we can treat others with love is to heal the guilt within us that says we are not worthy of love. This is original sin: the capacity to desire and be desired distorted into resentment, guilt, where each person becomes a caricature. There can be no enemies before the altar. There can be no false witness. The inward movement of this is that original sin produces self-loathing—a guilt of being loved. The will to power—the libido dominandi—is the natural Hobbesian consequence. We must make ourselves worthy of love because we have no inherent worth. We must trick people into loving us.

I wondered what bothered me, crossing coming out of Santa Lucia and then crossing the Guidecca canal, seeing these statues of Christ as Redeemer on top of San Simone Piccolo and Il Redentore. I saw it again and again, over the coming days, all over Venice. It is Venice’s Christ, just as Florence’s may be the Man of Sorrows.

One aspect that I dislike is that it’s too close to symbols of virtues, inherited from the gods of antiquity. Naturally, Il Redentore is Palladius’s church. I saw it first from the water and then visited the next morning, after waking up in a hostel with medieval wooden beams inches from my head. Close up, I couldn’t see Christ at the top. I could see a figure holding a cross and a cup. Fortune? I may be wrong, but this does seems to be an image of Fortune; not the cup that passed from him, not the Eucharistic chancel, but the cup that riches may flow from… Too close to prosperity gospel.

Accentuating is the pagan association is the statue atop the Punta della Dogana, just across the Guidecca canal. They play off each other. Henry James calls her ‘This Fortune, this Navigation, or whatever she is called—she surely needs no name…’ — who cares, really! It is indeed a statute of Fortune by Bernardo Falcone, 1677. The Museum guide at the Salute told me it had been poorly restored lately and its future was uncertain. Not ever so fortuitous.

It makes sense that a city so precarious is concerned with fortune and blessing itself against disaster, just as the city of Naples has developed a devotion to its patron St Gennaro whose blood, if it liquifies on his feast day, is a sign of the city’s protection in the coming year. I also learnt from a recent Richard E. Grant documentary that the time of the blood’s liquefaction is used to play lotto.

Il Redentore was built as a votive church to thank God for deliverance from the plague between 1575 and 1576, in which some 46,000 people (25–30% of the population) died. But it’s unclear whether a votive is something left in gratitude or an offering, a burnt sacrifice. Christ already made good on all our guilt. Votives, devotions, pilgrimages, all of these are meant to be done in the spirit of thanksgiving and hope for interior conversion, not to appease an angry God or implore his victory against the dark and chthonic forces of nature.

The more I saw this image, in gift shops and in churches, the more sinister it felt to me. The resurrected Christ had not come as a kind of pagan Asclepius. He had come to destroy death. It even appeared on top of a reliquary of the precious blood, which supposedly came into the possession of the church of the Friari in 1479 from the Commander of the Fleet to Constantinople. It is not usually made visible to the public and matches the style of the altar which was built to house it, in 1711. It is topped with the recognisable Redentore figure. This gives me reason to believe that the relic may be real but the reliquary is Venetian and of a later date. I may be wrong about the silver frame but the golden reliquary containing the Precious Blood itself seems to be Venetian on the basis of this image, which would not have been found in Constantinople in the 15th century. Zoom in and get a close look at this reliquary and the figure on top because I’m going to be talking about it a lot.

At the high altar of the Salute, where pilgrims trample the floor on St Cecilia’s Eve every year, there is a gorgeous Byzantine icon of the Theotokos and Chid. She is 12th or 13th century, titled Panagia Mesopantitissa, and erected in San Salute in the 17th century—another church build after an outbreak of plague devastated Venice in 1630. The Church in English is called Our Lady of Health.

In the sacristy, which is worth the small fee, there were several images of the type I’m interested in.

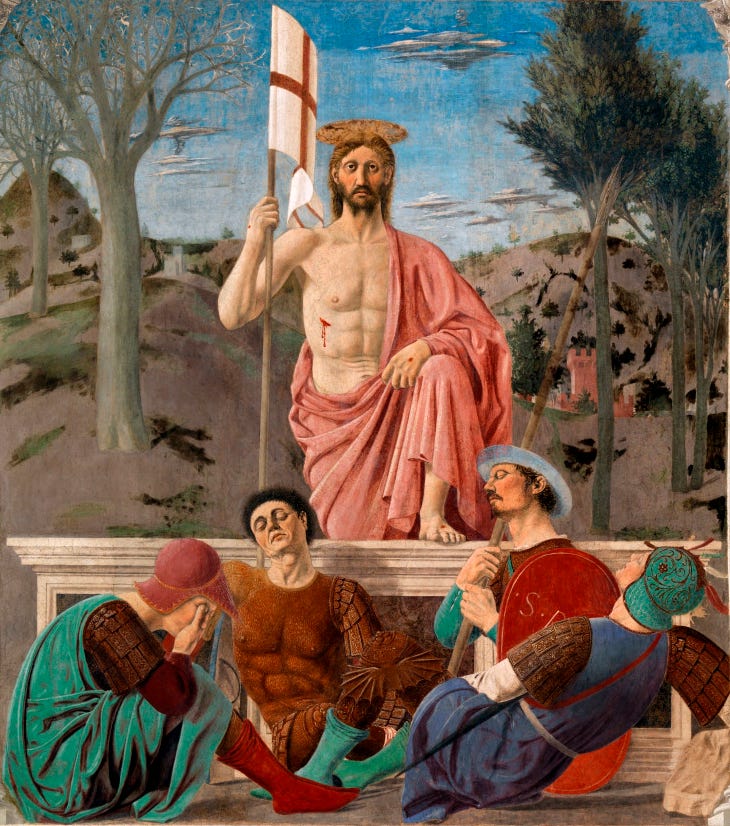

The museum guide was very helpful and spoke impeccable English but unfortunately I’ve forgotten who painted the first one. As it’s very bad, I won’t search further. The second is interesting—a sixteenth-century painting by Paris Bordon. Presumably (or scandalously), this was painted prior to the Council of Trent’s (1545-4565) ban on depictions of Christ hovering or floating above the tomb, demanding that his feet stay (as in the older tradition represented by the first painting) firmly on the ground. I imagine this has something to do with mixing the resurrection with the ascension. But obviously the artist in the first image has recently discovered perspective (or skateboarding) and is having a great time. Depictions of the risen Christ were meant to have his feet on the ground, either stepping out of the sarcophagus or standing upright and holding a banner. You can see a Tintoretto image of the floating Christ here (there are much worse ones):

There’s another interesting example here, after Titian. So this was definitely a theme developing in the Venetian renaissance. Who is this Christ? He isn’t recognisable from the Gospels. He’s ethereal, angelic, but at the same time more Roman Demi-God than Chalcedonian Two-Natured Christ.

The pagan and Christian figures around the city reflect each other saying: protect us: Don’t let us die. Save Venice, one of the cities most vulnerable to climate change. But Deus vult—if it be not my cup. This is the prayer we’re asked to say constantly. One of the prayers I try to say daily is the prayer of self-abandonment by St Ignatius:

Take Lord, and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding, and my entire will, all that I have and possess. Thou hast given all to me. To Thee, O lord, I return it. All is Thine, dispose of it wholly according to Thy will. Give me Thy love and thy grace, for this is sufficient for me.

For Freud, the drive for self-preservation, Ananake, along with Eros, is one of the essential drives for the creation of civilisation—a civilisation which represses boundless, murderous impulses; Freud likes repression, or at least knows it’s necessary. But if Christ destroys death he destroys Ananake. There is no more need for self-preservation. This is why, of course, the martyrs show us the foretaste of the kind of life we will share in the City of God. They have no regard for their own lives. Their beings are entirely geared towards eternity. Their passiones matter, not their acta, though someone capable of such self-renunciation tends to have lived with holiness.

How can we live as if the resurrection is really true? Really true? As if there really is no more death? Dom Sebastian Moore says that the disciples must have felt an envy of God. He’s similar to Simone Weil here. ‘The metaphysical inequality between creator and creator, which has been translated into the Master-Slave paradigm, is unbound. With God dead, with God powerless, with God no longer God, this movement of the soul would cease.’ Dom Sebastian seems to think that the death of God-qua-God is necessary for this metaphysical change to take place. Here he errs from orthodoxy (only Jesus’s human nature suffers and dies) and I don’t think he needs to; Weil does in much the same way, though her theology hangs on it.

What Dom Sebastian wants to say is that the victory over death creates something entirely new. Only absolute loss and absolute return of hope could have created the Jesus movement which would inspire the Evangelists and Apostles and all the saints and holy men and women who came to believe that Jesus was The Way. I count myself among them. Dom Sebastian is using Schleiermacher’s term ‘God-consciousness’ to say that there had been, in this loss and resurrection, a displacement from the God who kept guilt overpowering, to Jesus, who broke guilt and allows for authentic love relations. This is all a bit theologically suspect.

But there is something here. It’s one thing to believe in the resurrection with your head. Not many will even admit that anymore. It’s another to believe it with your heart. Do I? How would I live if I did? I would be like a St Anthony. That’s it, isn’t it—if I really believed in the resurrection, with my whole heart, I would be a saint.

Even though it was John’s account of the resurrection that convinced my head, at least enough to be baptised, the conversion of my heart began with the Incarnation. It began with Midnight Mass at St Catherine’s in Pontcanna in Cardiff one Christmas Eve, where I’d dragged my mum, never previously having had any interest in Christianity or churches. I received a blessing. Then I tried to jump off a bridge.

I can’t explain what happened there. Maybe it was because I’d watched It’s a Wonderful Life and I was very drunk and using drugs at that point in my life. But I think grace touched me then for the first time. I got a section 136 and taken to a police station. I got some Ryan Atwood style police trackies and got sent home. A friend of mine, Iggy, died jumping from that same bridge a few years later.

I’ll write more about this in part III. Not about my friend, but about being a Christian and having spend so much of my life wanting to die. It’s a difficult one and touches many people I know so I’m going to take my time. But I tried to kill myself again on Easter in Venice and I almost succeeded, so despite the trauma that followed in the psychiatric ward, I am immeasurably grateful to God and all his ministers on earth who give so much to work in the caring and medical professions. I am also grateful to Rosa, my landlady, who told me about her depressions and said that seeing me there as we waited for the ambulance reminded her of herself. I think she’s in her 80s and her house is full of Marian iconography. She let me chalk her door in the traditional English way with blessed chalk from the Oxford Catholic Chaplaincy which I was still carrying around in my bag, for some reason, having forgotten to bless my own door. Maybe it was meant for her; she lives with her adult sun, who is autistic and non-verbal, and seems to live with the most devoted verve of anyone I’ve seen.

Isn’t this the greatest Christian call—to go out and say, there is no more hunger, there is no more sickness, every tear will be wiped away… To live as if this is true? Did the disciples believe it, even having witnessed it? I think the fact that it survived to be the faith today must be evidence that something had changed so profoundly in their hearts that guilt and self-preservation hold nothing over them. Their lives can be wholly gifts of love.

It makes sense that guilt is the first sin because how could a person allow the fear of death conquer themselves to forget something so extraordinary. It must be built it. It can’t be the case that we’re entirely freed from it by baptism. But I found it interesting to think about through Lent. In what sense do I live as if death has been defeated? I am usually Thomas, craving more signs, relying mostly on the sacraments that all this insane faith means anything and I’m not wasting my life chasing illusions. But what if I really lived as if there was no more death? I would not worry, I wouldn’t prepare, I wouldn’t be anxious about anthything. As long as my head is stuck with worrying about anything in this world, my heart hasn’t grasped the resurrection. God, grant me the serenity…

The incarnation got into my heart not through apologetics. It just made sense that God would be born a vulnerable baby. That He would come and share in the world He had made, not as a victorious lord but an anonymous child. It was In the Bleak Midwinter that I believed in. ‘Enough for him, whom cherubim / Worship night and day, / A breastful of milk / And a mangerful of hay.’

The resurrection is not a victory in the ordinary sense. As I say in my landlady’s thirteenth-century palazzo, listening to the Stabat Mater playing from the TV-set in the other room, I started researching. In my deep-dive into the art history of the Christ as Redeemer image, I found that it was unknown before the twelfth or possibly late eleventh centuries. Some Carolingian Gospel books show representations of the Church or Synagogue carrying banners.

But in the West, representations of the resurrected Christ began with the empty tomb, the women, the noli me tangere scene, the road to Emmaus and the breaking of bread, the doubting Thomas reaching a finger towards the side wound, and the restoration of Peter. It was relational. More than anything it was strange, nothing like earlier narrative encounters with Christ. He wasn’t followed. He appeared and disappeared. He was unrecognised and recognised in spare moments—when he said Mary’s name, when he broke bread with his tired and confused friends. This kind of victory is more like the rosa mystica, a strange undying bloom. At Via Crucis at San Marco I tilted my head and followed the story. There was Christ sat in Judgement (after his ascension) but there were no triumphal risen Christs here. That is simply not what the resurrection means. A nun snuck over to behind the patriarch to get a service sheet for me so I could follow along in Latin and quite well in Italian once I had the tune.

Many have the same issue with the ‘Resurrexifix’, a modern processional cross that collapses the resurrection and crucifixion and seems to miss the significance of both. In his book The Meaning of Icons, Vladimir Lossky says that the church does not depict the resurrection because it was ‘inaccessible to any perception’:

The unfathomable character of this event for the human mind, and the consequent impossibility of depicting it, is the reason for the absence of icons of the Resurrection itself. This is why in Orthodox iconography there are, as we have said, two images corresponding to the meaning of this event and supplementing one another. One is a conventionally symbolical representation. It depicts the moment preceding the Resurrection of Christ in the flesh— the Descent into Hell; the other—the moment following the Resurrection of the body of Christ, the historical visit of the spice-bearers to Christ’s sepulchre. (p. 186)

So where did the Redeemer come from? One of the earliest example seems to be this manuscript initial in MS. Ashmole 1525 fol. 014r, probably c. 1210-1220 at Canterbury. Here Christ is interceding for the dead to His Father from his tomb (or perhaps His Father is giving him a helping hand). This probably draws on earlier images of the Harrowing of Hell where Christ does have that military garb and standard in his role as Victor over death. But he’s not shown in this way outside the Hell context.

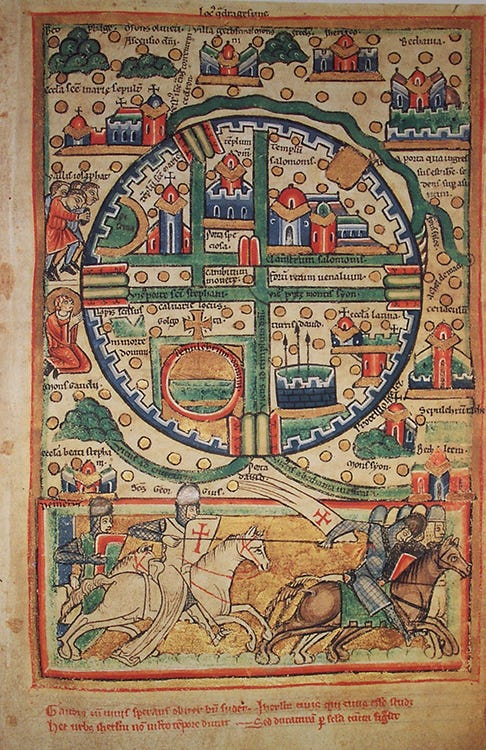

These kinds of images become very common in the Italian renaissance. This is Piero della Francesca in 1460 but he’s by no means unique. The feet are still on the tomb, though, not floating, but the banner is there. It’s always the St George Flag, which the English of course know as their own. It was also used as the flag of the Republic of Genoa in the 10th century, but chronicler James of Vitry says that the flag had been adopted in 1188 as that of the English and French armies who went to fight in the second crusade (earlier, by the way, than the manuscript initial above). Image of St George carrying this flag are obviously very common from an early date, but I’ve struggled to find Christ holding the type of flag that would become so common in the Redeemer image. There are, however, images of crusaders holding these banners. This map of the Holy Land featuring crusading soldiers below, for instance, dates from 1200-1200. Presumably these are the flags mentioned by James of Vitry.

It seems likely, even if depictions of Christ as Redeemer carrying a St George’s flag seem not to date from an English context, that the visual experiencing of crusading were influential on Italian art. Christ holding a flag in depictions of the Harrowing of Hell, combined to produce a image of the Redeemer with a particularly military, defensive emphasis. This is Christus Victor, victor over death. No wonder that this image would be invoked in times of the plague.

With regard to Christ hovering above the tomb, as seen in the many Titians and Tintoretto’s across the city’s churches, H. Shrade, in 1932, held the view that depictions of Christ hovering above the tomb began in Italy in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, with the earliest example of the type possibly associated with Giotto’s circle.1 M. Meiss rather, gives the first example of the hovering resurrected Christ in the Spanish Chapel in Florence by Andrea de Firenze in 1366-67.2 All are already shown with the distinctive red cross banner. Elly Casee and Kees Berserkik that these floating images, seen in grand scale on frescoes, were first found in manuscript illuminations—big images tend to begin small. That these manuscript illuminations come from the first quarter of the fourteenth century undermine Shrade’s argument that they began as a triumphal response to the experience of the Black Death, when artists in the third quarter of the century were supposed to have focused on more supernatural elements of the Christian story. The images below are taken from Tuscan Sacramentaries, but the authors argue that there are earlier (less accomplished, to my eye) versions from German sacramentaries.

There are also some very interesting Carolingian reliquaries showing the Church or Synagogue collecting the Precious Blood while holding flags, so it’s possible that the Friari reliquary may be drawing on that distinct tradition rather than the Venetian Redentore, but I doubt it because the images have a far less triumphant quality. If we disregard the Carolingian reliquaries, this flag seems to be influencing images of Christ on the content mediated through the experiences of the second crusade. The crusading association also makes it very unlikely that the banner on the reliquary was of Byzantine design.

Il Redentore, properly Chiesa del Santissimo Redentore, is of course one Palladius’ most famous facades, hugely influential on neoclassical architecture, and there remains a tradition of constructing a pontoon of boats once a year to cross from the main Island to the Guidecca, on the Festa del Redentore, the third Sunday in July. It represents a moment in the counter-reformation where art, ritual, architecture and popular practice turned from penitence to celebration. Not a decisive moment, of course, but a significant one; one which I think has important implications for how we think about the Risen Christ. Is he a figure celebrated with feasts and fireworks, who saves us from plagues? Or is He Someone who has made fear of plague meaningless. Churches like this cling to ananke, self-preservation, to fear of death. And ultimately, they cling to guilt, which is that refusal to give oneself wholly to love. The saints like St Anthony of Padua, who stayed with the sick even if it led to their own deaths, understood this. There are shrines to St Anthony in every Venetian church. These are the tensions in Venetian church art and architecture; and, of course, the tensions within our own souls.

Returning to Dom Sebastian Moore (I must try to track down his other books if they’re as good as The Fire and the Rose):

There is a difference between the death of God experienced by the disciples during the Good Friday period and as understood once the resurrection encounters have continued. After Easter, when God is not only alive again but alive for the astonished soul as it were for the first time, the meaning of his having died is understood. It is the behaviour of the lover. Human guilt, since the beginning of human time, has conceived the infinite as infinite power over against human weakness. This is the great projection, the primordial example of that guilt-projection of shadow onto the withdrawn-from other which permeates human society. It is so strong, it entered so deeply into and reshapes the very conviction of God’s reality, that only the surrender, the death, the non-self-insistence, of God Himself can break it.3

Moore says something interesting about how this moment of apprehension and bewilderment at God’s weakness is exactly what’s needed for faith to permeate; ‘infinite love capitalises on that experience and confirms it as an encounter with himself as the surrendering lover.’

I’m still not sure what to make of this. Is this the logical conclusion of kenosis, that God makes himself weak before us so that we might choose Him? Is this the exact opposite of the creation story? What if rejected—how can God stand blows? He does, of course, but orthodox Christianity holds that they pertain only to his human nature and can be said, in a sort of metonymic sense, to be done to God. But Moore seems here to be suggesting that the Godhead itself must sacrifice Himself to reshape his own reality.

He comes very close to Weil when he says that nothing ‘no instruction, no intuition, no vision even, can dislodge guilt from its central position in the human soul, whence it directs the soul’s perception of God. Nothing short of catastrophe can do that.When the catastrophe has done its work and left the soul in pieces, no longer holding itself together under the dreaded infinite powers, then at last the Absolute can be encountered not as power but as love: The Absolute encountered as love, not by any equation that the mind or heart of man can dream up, but in the psyche. The immemorial human psyche, home of eros, of guilt and of all the marvellous and conflicting movements shaped by those two forces, encountered the Absolute as love. The shock waves of that explosion are to be felt on any page in the New Testament.’

Venice is a of slow city of catastrophe. Its empire and trading power gone. But it was the same time that Venetian Renaissance art flourished that we find these images of Christ which suggest that a real sense of the resurrection has been lost. The libido dominandi has taken over, which must be so tempting when surrounded by reminders of your former grandeur. I felt a strong awareness that these things had gone together, though I’m not sure of the causal direction. I think I do believe in the resurrection now, though, in a way I didn’t when I first became a Christian. It’s gone from head to heart.

Does this mean we have to live permanently in catastrophe? The liturgical year doesn’t allow it. But Eastertide, as a period of rest, reading, awe, feasting, wonder, is meant for this purpose. Go and read the Gospels, especially the post-resurrection accounts. Let the extraordinary fact of their existence, their permissibility in this world, sink into you. Noli me tangere — but we have forty days with Him, in this strange, unprepared for, impossible state. Keep your eyes open for Angels.

I know there’s a bit of Nestorianism here and I’ve been thinking about Chalcedon and Ephesus a lot — please chime in w the comments! Esp if you’re interested in kenosis. I just can’t really get my head around the idea that agony and empty and death are only experienced by a part of Jesus. And yes I’ve read Leo’s tome. Genuinely looking for good reading on this that’ll help me think about it.

Bibliog. var. but Cited in Cassee, Elly, et al. “The Iconography of the Resurrection: A Re-Examination of the Risen Christ Hovering above the Tomb.” The Burlington Magazine, vol. 126, no. 970, 1984, pp. 20–24, was particularly helpful.

Rose, don't go anywhere, I love reading your writing. This is great art criticism. And that you've actually written this after that is, well, pretty miraculous.

This is a phenomenal piece, I absolutely loved it! Your thoughtful analysis of art, reflections of Christ as Our Redeemer and the reality of the ressurection are all topics which I have been deeply resonated in and are core to how I have always understood my faith, especially, now as a postulant in an order dedicated to Christ the Redeemer, the Redemptorists.