At some point in the last five years, post-war Europe ended, though it’s difficult to say exactly when. One can point to Brexit or to the Russian invasion of Ukraine or to last summer, when a British Prime Minister dipped out early from the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of D-Day the same week that National Rally took 31% of the French vote in the European Parliament Elections, finally breaking the cordon sanitaire that had placed far-right parties beyond the pale of mainstream French politics. Yesterday’s election of the first American pope, on the 80th anniversary of Nazi Germany’s unconditional surrender, perhaps marks the definitive end.

The post-war European epoch was founded on a commitment never to allow fascism to reoccur. It was to this end that the Council of Europe was formed in 1949, followed by the European Court of Human Rights and other institutions which enshrined liberal democracy and market capitalism as preconditions of membership in the new Europe. After the war, General Patton famously said that he ‘had never heard that we fought to de-Nazify Germany—live and learn.’ Opposition to Nazism was not necessarily a motivation for the Allied fight against an expansionist Germany, though this was arguably a decisive factor in Britain remaining in the war after the fall of France in 1940. It was only after the war, when the full scale of Nazi atrocities became known, that anti-Nazism became a foundation stone, alongside the maintenance of peace, of post-war European culture and policy.

There is almost no area of European intellectual enquiry untouched by this commitment. In history, philosophy, theology, every field and sub-field is caught up in undermining the intellectual foundations of Nazism or reckoning with how the events of 1933-1945 came to pass. This meant, firstly, that European nationalisms and romantic sentiment for the particularity of the past had to be rejected. But it also meant that Europe, despite the influence of American money and culture pushed by the Marshall Plan, couldn’t adopt American culture wholesale. To protect itself against a repeat of the past, it had to retain an understanding of that past and its power. The Europeanism which developed after the war had to steer a delicate course between nationalist particularism and American homogeneity. It had to keep a sense of what made European histories distinctive while neutering affective attachment to nations.

My generation, those of us who have little connection to the Second World War, tend to miss how profoundly it shaped post-war Europe and its whole intellectual scaffolding. Levinas famously said that theodicy was impossible after the Holocaust; Adorno said that it was barbaric to write poetry. There was no history written after the Holocaust that was not in some way a response to it. Post-war Europe was a different world to what had come before. And the tragedy was so complete that there could be no historical enterprise that was not in some way an attempt to understand it, to dispel its intellectual foundations, or to build a new intellectual edifice in the place of the one which had allowed Nazism to arise.

Now, the generation whose hearts and minds were shaped by direct experience of war are no longer with us; the European institutions created in the aftermath of the war are crumbling, failing to adapt to a globalised and multipolar world which their constitutions could not anticipate.

Last week, I impulsively booked a flight to Guernsey. I boarded a tiny plane from Gatwick and overheard passengers talking about coming back from holiday to a three-day work week—bank holiday on Monday and Liberation Day on Friday. Eighty years ago today, one day after the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany and the end of the Second World War, the Channel Islands were freed from five years of occupation. I knew little about this and hadn’t ever given much thought to the fact that part of United Kingdom had been under Nazi control. I walked the length of the island, and everywhere I went I saw homes decorated with Guernsey flags and Union Jacks in advance of the Liberation Day parade.

There are two good war museums on the island, the German Occupation Museum which is a short walk from the airport and La Valette Underground Military Museum, the latter of which has a more extensive collection. The Channel Islands were occupied from the 30th of June 1940, after the British government had evacuated its army from the continent and made the decision to demilitarise the islands, considering them of no military significance and too costly to defend—rather, they would be a burden for the Germans to manage and a drain on Hitler’s military capabilities. 25,000 civilians were evacuated to mainland Britain, but the British government encouraged many to stay—over 40,000 people remained on Jersey and just under 25,000 on Guernsey, 470 on Sark and 18 on Alderney. The British government did not officially inform the Germans that the islands had been demilitarised, assuming that the news would reach them through unofficial channels. It did not and, as a consequence, ports on Jersey and Guernsey were bombed with 44 civilian casualties before a reconnaissance pilot landed on Guernsey and found that it was undefended.

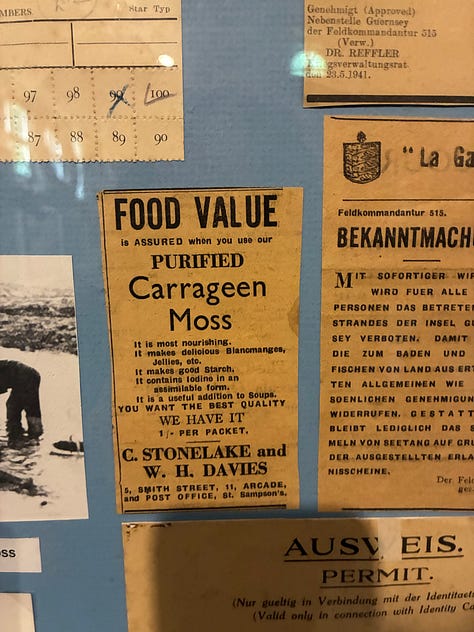

What followed has been called a ‘model occupation’—Hitler wanted, at this stage, to use the Channel Islands as a propaganda coup to demonstrate to the British that life under the Nazi regime would not be oppressive but rather well-ordered and civilised. There was little organised resistance as on the continent beyond scattered attempts at sabotage and some successful escapes—there was one German soldier for every two islanders and the occupying government made clear that any resistance would result in reprisals against the whole population. Successful escapes were followed by greater restrictions on civilian life—access to beaches was forbidden and permits were required for fishing; fishermen were eventually required to take a German soldier with them whenever they went out to sea. They were also prohibited from fishing in the deeper waters further out, which meant that catches were less plentiful, exacerbating the issue of limited food supply. All livestock had to be registered, and from the beginning of occupation the black market dealt in unregistered pigs and cows. Theft was rampant and despite the curfew some farmers tried to stand watch over their cows at night to prevent secret nocturnal milking (largely from German soldiers, whose diets were also rationed and felt able to steal with impunity.) With German supply lines cut after the D-Day landings in June 1944, soldiers and islanders alike faced starvation and survived by eating seaweed and domestic pets until a Red Cross ship was able to deliver emergency aid in December.

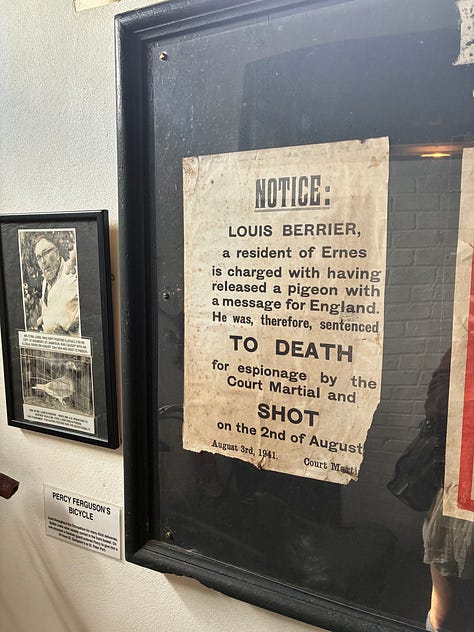

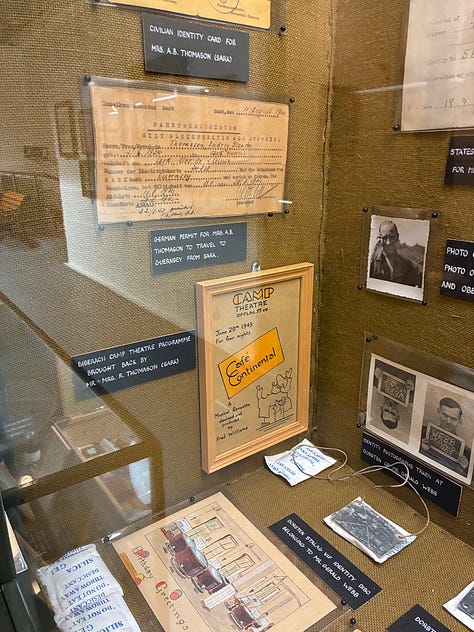

The initially lenient treatment of the Channel Islanders ended in 1942, when Hitler, enraged at the British internment of German civilians in Iran, personally demanded that civilians be deported to internment camps in Germany as an act of retaliation. 2,300 civilians were deported, mainly to purpose-built camps in Biberach, Laufen and Wurtzach. By the end of the war, 45 people had died in the camps. From 1942, Germany also began operating work camps and concentration camps on Alderney, where prisoners of war were sent, the majority of prisoners being Russian and Eastern European. As records were destroyed before the end of the occupation, it’s difficult to determine the precise number of prisoners and casualties. A report commissioned by the British government in 2023 determined that ‘the number of deaths in Alderney is unlikely to have exceeded 1,134 people, with a more likely range of deaths being between 641 and 1,027.’ Civilians from the Channel Islands were also imprisoned or executed for resistance activities.

Last year, I visited the Museum of the Surrender in Rheims, formally Eisenhower’s military headquarters, where the first official document of unconditional surrender was signed by General Alfred Jodl on the 7th of May 1945. A second surrender was signed under Soviet supervision in Berlin the following day. The room where it happened has been left as it was, the war maps and tallies still on the walls. Walking around Rheims, everywhere you look are buildings pockmarked by bullets. London also bears the scars of the Blitz, but it feels harder to understand how somewhere like this, where war was fought on the ground and where so many reminders still remain, was able to rebuild and redefine its identity so quickly after the war’s end.

The culture of post-war Europe was characterised by a pervasive historical amnesia punctuated by sharp and quickly suppressed flashbacks. This is the symptomatology of trauma expressed on the level of culture. In Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire, angels wander vaguely around a divided Berlin from which God has departed. The humans and angels alike are unmoored, individual, dislocated from place and history. We hear the inner thoughts of Marion, a trapeze artist:

I couldn't say who I am. I don't have the slightest idea. I have no roots, no story, no country, and I like it that way. I'm here. I'm free. I can imagine anything. Everything's possible. I only have to lift my eyes and once again I become the world. Now, on this very spot, a feeling of happiness that I could keep forever.

As the memory of the war fades, so does the amnesia. This year’s memorial celebrations have both a detachment and a directness inaccessible to people who had lived through atrocities. It’s possible to say things that couldn’t have been said even ten years ago. It’s possible for Kanye to release that song. In the second part of this series, I’ll look at a particular area of European historiography and what recent developments in that field indicate about the Europe’s possible futures. One possibility is a resurrection of fascism and a new nationalism, different in being directed against mass immigration from countries beyond Europe rather than the pitting of European nationalities against each other. The other possibility is a reinterpreted universalism, transitioning from pan-European institutions to global ones, from a European sort of deracination to an American one. There are other options. But whatever follows will be defined in relation to new reference points; it will be something other than a long coda to the Second World War.

Over the last year, I’ve watched a lot of films and documentaries about the war. It’s one of the best coping mechanisms I’ve found when I’m feeling hopeless and suicidal—it gives me an immediate sense of perspective and I find it consoling to know that people lived through unimaginable horrors and somehow came through them, built new lives and carried on. I got some criticism for saying this on Twitter, and I understand why; it can seem callous or disrespectful to use the most unspeakable experiences of others for a kind of personal gain. But it does work, so I’m sharing some of the films and series in case it’s of similar use to others, or just for general interest:

Berlin 1945, a very good documentary series covering Berlin through the final year of the war, interspersing newsreels with diaries and artefacts of ordinary life (I didn’t realise how many commercial films were still being produced and screened in German cinemas even until the end of the war).

Berlin 1933, which isn’t about the war but which I recommend anyway because it’s very well done.

Shoah, a nine-hour documentary about the Holocaust which was controversial for its portrayal of the anti-semitism and complicity of Polish civilians.

Hell in the Pacific, a four-part documentary series about the Pacific Theatre, which I knew very little about beyond Unit 731. This series is particularly disturbing because Japanese soldiers who participated in the Rape of Nanjing are interviewed and talk openly about some of the worst atrocities ever committed with little to no remorse. Totally unlike anything you’d hear from Germans or Italians so it’s quite shocking.

Roberto Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero, filmed on location in the ruins of Berlin immediately after the war, where the extras are literally starving people scavenging for food. One of the bleakest films I’ve ever seen.

Rome, Open City, another in Rossellini’s trilogy of post-war neorealist films. Shooting began in January 1945 before the war had even ended and the Salò Republic was still standing its ground in the north. An incredibly beautiful and moving film. (Pasolini’s Salò should obviously get a mention in this list but I saw it years ago.)

The Darkest Hour, a twee film which I didn’t enjoy (the scene where Churchill consults a tube carriage of Londoners on whether Britain should stay in the war is particularly silly) but still interesting.

Dunkirk, the only Christopher Nolan film I’ve really loved. Genuinely didn’t know anything about Dunkirk before watching this and had no idea that private civilian boats had been used to evacuate soldiers from France.

D-Day 80: We Were There, a documentary from last year interviewing British D-Day veterans. I was particularly haunted by one veteran who’d lost six friends in Normandy and said, ‘Sometimes think was it all worth it. I look around at the world today and you know—was it? I don't know. I wouldn't like to say.’

Number 24, a very good film about Norwegian resistance leader Gunnar Sønsteby. Highly recommend this, I just stumbled across it on Netflix and it doesn’t have a Wikipedia page in English so wasn’t sure if it would be any good but it’s stayed with me long after watching.

SAS: Rogue Heroes, another surprisingly good series about the bravery, nerve and insanity of the first SAS members.

The Zone of Interest, obviously an excellent film with some of the most disturbing sound design I’ve experienced.

Lost Home Videos of Nazi Germany, really interesting two-part BBC social history documentary with some amazing bits of footage, interesting for giving a look into how ordinary people experienced the Nazi regime.

Re. Film/Documentary recommendations:

The Way Ahead - Probably the best drama/propaganda about the British Army, specifically following conscripts from initial mobilisation to battle in North Africa. Understated performance by David Niven and Trevor Howard's first appearance on screen.

The Cruel Sea - Following anti-submarine warfare during the Battles of the Atlantic and the Arctic, particularly the toll of command and the moral responsibility of taking lives. Contains probably the most accurate and disturbing depiction of PTSD hallucinations that I've come across yet. Despite that, or perhaps because of it, the best film about the Royal Navy in the Second World War.

A Bridge Too Far - Superb depiction of Operation Market Garden focusing on British and Allied Airborne and XXX Corps hammering up the road to Arnhem to meet them. Fantastic performances by immensely talented actors (Caine, Hopkins, Bogarde, Connery, Hackman etc). Immensely moving.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp - Powell and Pressburger's best film. The best film about belle epoque Britain and Britons. Simply wonderful.

A Matter of Life and Death - Cheating slightly here but it is about an RAF pilot and the cultural angst over Britain slipping behind the United States. Roger Livesey is, as always, brilliant and it is also one of the best films ever made.

This was a very insightful post. Having grow up in Germany, World War 2 was not only the cornerstone of our historic education, but the entire myth underpinning society. The worst one could call someone was a Nazi - and we knew that there were Nazis hiding everywhere, under strange stones, in every fringe political movement. Now the leader of Germany's far right part is a Lesbian women, married to a Sri Lankan. She is a Nazi in the eyes of my university professors. At the same time, somehow, the myth is seeming to loose power among the young. You can see this in in a huffed criticism of Israel among the left - unthinkable in the past. On the right, questions of nation, belonging, pride, masculinity, are asked again - unthinkable in the past. At the same time, the ghost of Nazism still lives throughout our collective memory, but increasingly unrecognisable. Kanye praises Hitler in direct reference to his blackness, after all.