excavated poetics

on sacramental ontology, history, David Jones, John Cale, Joseph Ratzinger, Christopher Dawson and Sinead O'Connor

Over the last month I’ve been working on a couple of longer pieces (which are to come). I’ve also been recording a bunch of podcast episodes, which you can listen to on the In Our End Times Patreon or on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. I spoke to Levi Roach, a medieval historian at the University of Exeter, about charters, diplomatic, early medieval kingship and eschatological thought. I spoke to

about Mary Gaitskill, God and hysteria. I spoke to Francis Young of about the crisis of ritual, liturgical reform and Paganism. And, in the most recent episode, I spoke to Magdalene J. Taylor of about the perceived crisis in dating and relationships and how to get out of it. Subscribe to stay up to date with new episodes—hopefully sticking to a fortnightly release schedule.I also went back to Wales for a while and have been reading lots of Saunders Lewis and David Jones. I found this video (one of those brilliant BBC Third Programme offerings, this one produced by Tristram Powell and Melvyn Bragg):

Jones talks about making things. ‘Thing’ was maybe the most important word for him, a rough translation of the Latin res, which for Aquinas was a transcendental attribute of being signifying its essence. Jones’s Thomism was formed through contacts with Dominicans in his intellectual circle, chiefly Jacques Maritain (another ‘Order man’), as well as Fr. Thomas Gilby O.P. and Fr Illtud Evans O.P. Asked why he became a Papist, Jones replies:

‘Even the Catholic religion weren't true, you'd almost have to become one... Because the whole notion of the arts, of making a thing and saying this represents, more than represents, is this other thing, in another form, is frightfully like, just by analogy, in the crudest way, the doctrine of transubstantiation, and that immediately connects, and the whole sacramental notion… The whole of life is a sign of something other, and that’s what is the difficulty of our particular age, I mean, it’s there, but it’s difficult, as it is in all periods of tremendous transition…’

In Jones’s essay Art and Sacrament, he argues that man’s essential nature is to be a sign-maker, a sacramentalist. He discusses the same idea in his preface to The Anathemata:

‘What is this writing about? I answer that it is about one's own ‘thing’, which res is unavoidably part and parcel of the Western Christian res, as inherited by a person whose perceptions are totally conditioned and limited by and dependent upon his being indigenous to this island.’

Jones opens his preface by quoting the introductory matter of Nennius's Historia Brittonum, where the historian says that he has gathered his material from a variety of sources so that this material ‘might not be trodden underfoot.’ Jones, like Nennius, saw that his task was ‘to allow myself to be directed by motifs gathered together from such sources as have by accident been available to me and to make a work out of those mixed data... If one is making a table it is possible that one's relationship to the Battle of Hastings or to the Nicene Creed might have little bearing on the form of the table to be made; but if one is making a sonnet such kinds of relationships become factors of more evident importance.’ He sees these signs in a sacramental fashion, so that knowledge of them does condition the art one makes, but that the things they signify may be evoked even by an artist with no knowledge of them, ex opere operato. The res has a transcendental existence which is unaffected by the presence or absence of valid signs.

The difficulty, however—this is the difficulty he’s hinting at in the video above—is that as sign-making creatures, we need to make valid signs to make any true sense of ourselves and our place in the world, in history and in relation to God and eternity; we need culture to be a vehicle to salvation. Like Saunders Lewis, Jones looked back to Britain’s ancient civilisation, its Christian Romanitas followed by an age of heroes and saints. Its landscape was full of buried giants, sleeping dragons, holy wells. It had been Catholic and Latin-speaking before it had been English. This ‘matter’ of Britain was the material from which a sacramental order could be fashioned. For Saunders Lewis, a founder of Plaid Cymru, the whole political project was to restore this gwareiddiad (civilisation). In a letter, Saunders Lewis expressed his belief that:

that his roots are in the earth, and entwined with the roots of his people; that a man's life is a moment in the long and slow process of his nation's life; that a movement has no beginning and no end because it has not being nor meaning in itself and by throwing himself into the life of his country and his people a man comes to know himself, to nurture his own soul fully and richly, and lives as an artist to the full extent of his consciousness.

I vividly remember being in primary school and picking up a copy of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood in the library. I read its beginning and thought oh, this is what you can do with language. The realisation that you could make combinations of words like ‘fishingboatbobbing sea’ and ‘organ-playing wood’ or control the pace of a sentence like this:

And you alone can hear the invisible starfall, the darkest-beforedawn minutely dewgrazed stir of the black, dab-filled sea where the Arethusa, the Curlew and the Skylark, Zanzibar, Rhiannon, the Rover, the Cormorant, and the Star of Wales tilt and ride.The lull and rhythm of the Welsh language and Welsh accent (listen to the way Richard Burton says ‘Star of Wales’ at 2.17 to see what I mean) points to a particularly Welsh poetics, where there’s a tremendous sense of language stumbling across something that was already there, a pre-existing rhythm. The poet’s role is to uncover the right words to disclose a picture already given (I think this is why David Jones stumbles over his words, like he’s painfully trying to get the right one, which is something I also do). Central to the Welsh bardic tradition is the notion of awen, which Rowan Williams has described as ‘a state of altered consciousness in which the poet receives knowledge of matters beyond what can routinely be learned.’ Awen has an implicit metaphysics—a sense that meaning is not created or found, somewhere out there in the world or on the surface, but is excavated from the land itself, from its deep drowned villages and mineshafts, the forests and towers swallowed up when drunk Seithennin neglected his duty. The image of Taliesin playing his harp and singing from the tallest tower as the waters rushed in. The notion of belonging is wrapped up with this poetics—a deep pessimism and melancholia, a belief that the fullness of meaning and the correspondence of all things was once present but has been drowned out by our own incompetence and unworthiness, our dereliction of our inheritance. It goes back to Gildas and the De excidio Britanniae, at least.

Reading David Jones’s Anathemata, I realised that everything I admired in Under Milk Wood (which is so different from the rest of Thomas’s poetry) was done first and better by Jones. Thomas said ‘I would like to have done anything as good as David Jones.’ He was a jealous poet; he wanted to write the Welsh Ulysses, but his success was the product of craft rather than genius. Think of the ballad recited by the Rev. Eli Jenkins in Under Milk Wood:

Dear Gwalia! I know there are Towns lovelier than ours, And fairer hills and loftier far, And groves more full of flowers, And boskier woods more blithe with spring And bright with birds' adorning, And sweeter bards than I to sing Their praise this beauteous morning. By Cader Idris, tempest-torn, Or Moel yr Wyddfa's glory, Carnedd Llewelyn beauty born, Plinlimmon old in story, By mountains where King Arthur dreams, By Penmaenmawr defiant, Llaregyb Hill a molehill seems, A pygmy to a giant. By Sawdde, Senny, Dovey, Dee, Edw, Eden, Aled, all, Taff and Towy broad and free, Llyfnant with its waterfall, Claerwen, Cleddau, Dulais, Daw, Ely, Gwili, Ogwr, Nedd, Small is our River Dewi, Lord, A baby on a rushy bed. By Carreg Cennen, King of time, Our Heron Head is only A bit of stone with seaweed spread Where gulls come to be lonely. A tiny dingle is Milk Wood By Golden Grove 'neath Grongar, But let me choose and oh! I should Love all my life and longer To stroll among our trees and stray In Goosegog Lane, on Donkey Down, And hear the Dewi sing all day, And never, never leave the town.

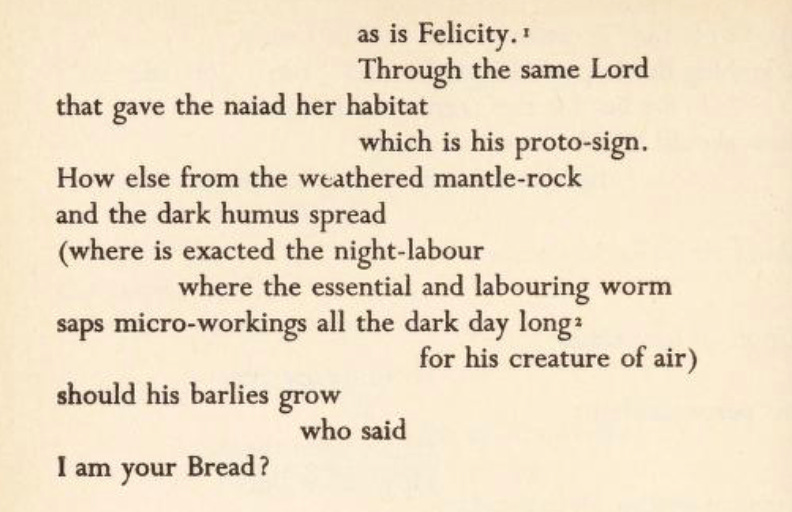

Compare this with Jones in The Anathemata:

The former is, of course, already a pastiche, voiced by a sentimental minister of religion. But that’s the mode that Dylan could do well. He was a love-letterer, good at turning a phrase to get a pint out of it, with a good ear for the smoothness of domestic speech, its manipulations and petitions. Jones, on the other hand, wasn’t trying to get anything out of it that wasn’t already there. His petitions are prayerlike, revelatory. ‘By Cader Idris, tempest-torn… Plimlimmon old in story’ makes you feel hearth-warm, like home-cooked food. Jones is an arrow to the heart, a clearing in the wood. He speaks with the awen which let bards stand outside time and speak within it, crossing lines that only the angels could. The bardic tradition has always associated poetry with prophecy, with revealed knowledge. A phrase like ‘here lie dragons and old Pendragons’, which in any other context would be hackish and parochial, is here given its place in the register of the muses. Jones’s geological forays in the first section of the poem, subtitled ‘Rite and fore-time’ emphasise this embedded, sacramental ontology. The Dies Irae mixes with semi-mythic kings (ver-tigérnus recalls Vortigern) buried beneath Snowdon in pre-Cambrian deep time, ancient beyond measure, always and already eschatological.

Jones is precise about how lines should be pronounced, giving extensive notes for non-Welsh speakers. Welsh mixes with English in modern and archaic forms as with Latin, Greek and Hebrew. Switching between them is effortful—Jones forces you to be his coworker. Even changing the mouth’s position in pronouncing the different letters and diphthongs of Welsh and English and Latin makes you strain and slip over words. Sêt, above, is a way of saying seat that only makes sense with a long-voweled accent. In favilla—a mind familiar with the pre-conciliar liturgy will switch to chant for these lines from the Dies Irae, familiar from Requiem Masses and the liturgy for All Souls’ Day. So there are rhythms and patterns that readers will participate in if they belong to this or that culture. There are phrases like O vere beata nox! and ‘This is the night’, quoting the Exsultet, which conjure memories of each year’s Easter vigil, each candlelit church where I’ve heard it sung (or sadly abbreviated and said in its short form, as in the Friari in Venice this year). There are words like môrforynion, which (as Welsh is prone to do), force the voice into metrical goose-step. There are etymological echoes, collusions between words of different times and languages and peoples; there are place-names, an encyclopaedic sense of the value of specificity, the folklore known by one or two farmers about the reason for the name of that hedge or oak tree.

I read The Anathemata on the train, going along the edge of the sea at Carmarthen Bay and through the sulphurous aura of the blast furnaces at Port Talbot. It was the last day of iron production for one of the furnaces, to be replaced by an electric arc furnace which will melt down and recycle scrap metal, the final whimper in the long, laboured death of the industrial age. The valleys deep green, raining in July, Margam mountain cloaked with mist; the old stone chapel somewhere up there hidden in tress, the space for a stone altar, hole in the wall for the unconsecrated elements. We don’t make things anymore. The artist’s problem of dealing in signs, quarrying and fashioning them, giving shape to things hidden and resting and half-asleep. The giants laid down, their eye-sockets lakes, having waded back and forth across the Irish Sea. The place to go and gather these signs seems perhaps to be chaos, the abyss, which is neither good nor bad but a raw potential energy for making and unmaking—the unmaking which unleashes insubstantial demons to wander through this world. Anyone who fishes here needs discernment. The lack of correspondence of things to signs feels like plummeting. But not just that break, which has been known about for a while, but now the forgetting—that barely anyone seems to notice that things don’t correspond the way they should, that this doesn’t seem to trouble them. That the world is other than it should be in an unbreathable, irrecoverable way, and that it feels impossible even to speak in this situation. The prophet lurches between mute periods and sudden revealed speech.

The preface to The Anathemata talks about this:

By ‘anathemata’, Jones recalls John Chrystostom's definition of the word as ‘things... laid up from other things’. He says connects art-making, as in the video above, with the Eucharist. ‘Something has to be made by us before it can become for us his sign who made us. This point was settled in the upper room. No artefacture no Christian religion.’ This attributes to us a huge sense of agency as co-workers not just in our own salvation, but in the corporate Christian culture by which salvation history progresses towards its end. In this passage, which closes the first book, the labouring worm joins in the work of salvation in the soil from which the barley grows to make the flour which will be kneaded by human hands to make the host:

Within this ontology, history has a decisive role. See the quote below, where Jones asks ‘where do we seek or find what is “ours”, what is available, what is valid as material for our effective signs?’ If, as he says, ‘the bulldozers have all but obliterated the mounds’, and the poet cannot find the material to fashion his signs, then the sacramentality of the world is rent apart. Within history, we have reached a moment where the symbolic order is no longer immediately available to us; it’s not just that we’ve forgotten the transcendental, but that the bonds between this world and the transcendental order have been loosed by this forgetting. We are no longer time-bound, but nor are we possessed of the awen of the bards; by taking ourselves out of time, we have flattened reality so that the correspondence between things as they are and things as they will be has been lost.

For a while I’ve been thinking about the metaphysics of the communion of saints. In Bede’s adaptation of Augustine’s six ages of the world schema, he discussed a seventh age, an age of the saints, which runs parallel to the sixth historical age and will finally be joined to it at the inauguration of the eighth age, which is eternity. This sort of ontology fits well with how Jones was thinking about art, wherein history corresponds to and communicates with an extra-historical mode of existence. Aquinas called this the aevum. The clearest point of contact between these modes, the sixth and seventh ages, is in the Mass, where our prayers are joined with those of the saints and angels, and especially in the sanctus. In the liturgy the sign is more than a sign; it is what it signifies. But the Mass belongs in time and isn’t discontinuous from the rest of its age, its culture. When Jones refers to the naiad’s habitat as the Lord’s proto-sign, he means that nothing is excluded from the sacramental order which has its focal point in the Mass. The earth and all its habitations, all the monuments and fragments of history, belong to and participate in the grand, ultimately conclusive mystery.

In Pope Benedict XVI’s Principles of Catholic Theology, he wrote:

Man finds his center of gravity, not inside, but outside himself. The place to which he is anchored is not, as it were, within himself, but without. This explains that remnant that remains always to be explained, the fragmentary character of all his efforts to comprehend the unity of history and being. Ultimately, the tension between ontology and history has its foundation in the tension within human nature itself, which must go out of itself in order to find itself; it has its foundation in the mystery of God, which is freedom and which, therefore, calls each individual by a name that is known to no other. Thus, the whole is communicated to him in the particular.

The disconnection between ontology and history was, for Ratzinger, ‘the fundamental crisis of our age.’ Jones’s circle were discussing ‘the Break’ in the twenties and thirties, it probably having begun with the First World War (and been consolidated and completed with the Second). I think this is what John Cale’s 1973 album Paris, 1919 is about. In A Child’s Christmas in Wales, he sings: With mistletoe and candle green / To Halloween we go... The hallelujah crowd... tripped uselessly around / Sebastopol Adrianapolis / The prayers of all combined / Take down the flags of ownership / The walls are falling down. Cale uses the language and landmarks of a Europe which had already passed, where time was folded into a ritual calendar and language impressed with the seal of Christendom, a common vocabulary where vernaculars mixed with the Latin and Hebrew of liturgy.

Sinead O’Connor does the same sort of thing in her music, invoking this mixed inheritance, the universal culture of Christianity and the particular national and regional cultures which stretch back to pre-Christianised peoples. On Theology, which is primarily a reworking of the psalms (itself a devotional activity), she identifies with other Christian traditions while locating herself in her particular Irish context. In Rivers of Babylon, a retelling of Psalm 136/7, the Babylonian exile becomes a symbol for her sense of having been exiled from Ireland, alienated and hurt by a Church and a nation to which she nevertheless belonged. In Out of the Depths (Psalm 129/130), she addresses God, asking ‘is it bad to think you might help from me? / Is there anything my little heart can do / to help religion share us with you?’ In this, she casts herself in a prophetic role similar to Simone Weil, who saw herself as having to stand outside the Church, to the point of refusing baptism, so that she could be a conduit between Gospel and culture, reaching those so alienated from the Church that they would never otherwise hear Christ’s message. Theology spoke with the voice of the Psalms, the exiled prophet, furious with God, persecuted, lamenting at the state of His chosen people, nevertheless certain of God’s unrelenting love and forgiveness. To do this, she drew on the vast resources of Christian culture, its scripture and liturgy, as well as its contemporary inculturation. Listen to her singing Hosanna Filio David, the Palm Sunday antiphon:

For Christopher Dawson, Catholic historian and the most influential figure in David Jones’s intellectual circle, ‘the schism between religion and culture’ was the central civilisational crisis. It could be remedied primarily through education, so that each generation could have an opportunity to encounter the wealth of Christian civilisational and culture which had otherwise passed out of memory. This was true also for Weil (I wrote about the importance of education in her thought back in March for the Mars Review of Books). Both Weil and Dawson placed an emphasis on the history of the Middle Ages; in A Monument to Saint Augustine (1930), Dawson’s contribution highlighted the relevance of the study of late antiquity to our contemporary age:

For the real interest and importance of that age are essentially religious. It marks the failure of the greatest experiment in secular civilization that the world had ever seen, and the return of society to spiritual principles. It was at once an age of material loss and of spiritual recovery, when amidst the ruins of a bankrupt order men strove slowly and painfully to rebuild the house of life on eternal foundations.

He came to understand sanctity as a driving force in history—an agent-focused philosophy of history, against the materialist interpretations in vogue in his time and the anthropologically-tinted functionalist interpretations which would follow. He saw the supernatural virtues of the saints as having a profound influence on culture, radiating out and influencing the whole character of an age.

This relates, again, to Jones’s metaphysical poetics; the saint’s life can be read, in Jones’s terms, as a work of art, a fashioning of material into useable signs which could communicate something of the transcendent reality. Casting back through Welsh history, it mattered that the land had been dotted with saints, that every Llan- place name marked a saint’s cult, that St Winifred had translated the raw material of a spring into a locus sanctus. By ‘anathemata’, he didn’t mean a fixed order of sacred things set apart from profane culture. He meant a process by which particular fragments were made sacred, which is to say made disclosive, by a process of artistic working.

Every age has its saints, and privately I’m building my canon of people who have been able to speak to an age and see beyond it, the awenyddion who have been gifted the authority to reveal. Jones and his contemporaries were modernists, and though they recognised the Break they were still working with the same raw materials as centuries of predecessors. What awen sounds like now, a century after the Break, when not only the symbolic order which came before it but the Break itself have been forgotten, is something that troubles me in the same way Jones was troubled. It is, as he put it, a ‘situational problem.’

Attention all book lovers!

We're working on a project called "Serendipity Ulysses," where we’re offering ad space within the text of "Ulysses" itself—a fun way to blend literature with digital media. We’d love for you to add your link and join in! Check it out: https://sulysses1.substack.com/p/serendipity-ulysses-in-a-nutshell

If you’re interested in writing about it, we’d be thrilled to feature your Substack post on our project’s resource page. Let us know what you think!

Heidegger refers to something usually translated as "the rift" (Der Risse ie the cracks), which is a fundamental (ahem) break between traditional culture and modernity, in "The Question Concerning Technology". His attempts to expose it and to revive culture are twofold: to expose the original meanings of terms that we use today eg that poetics meant "making" rather than subjectivity (and so he's out to "destroy" Kantian distinctions of thought and being); and furthermore, his etymological archaeology - or "excavated poetics" as you suggest - seeks to reveal the places where the deeper wound (or rift) between gods and men are reconciled. Do he sees poetics as ways of making visible again the "fourfold" character of Being, which includes visible and invisible dimensions and beings. Ultimately, he concluded that there was an inevitable "strife between earth and world", because humans focus their energies evermore upon materialism ie the false aesthetics of making pseudo-transcendence (eg money, and modern energy that is de-situated, "stored up energy" - ie technology). Rather than recognising the essentially poetic character of Being itself - since, as he suggests in various essays in the collection Poetry, Language, Thought, citing Hölderlin evocatively, "full of merit yet/poetically man dwells."

My understanding of this derives from my time as a graduate student in the department of architecture at Cambridge in the 1990s, where my teachers Dalibor Vesely and Peter Carl wrote at length about such problems as "Architecture and the Question Concerning Technology" (DV). Their work, and ours, was oriented more or less towards the potential revival of the remains of an ethical ontology of poetics; focused upon the fragmentary character of modern poetics, not only as a metaphor, but in terms of the actual ruins of urbanity where philosophical and architectural concern with ideas (eidos?) such as justice and difference might re-emerge from the chaos of the modernist rift-landscape - in the mind as much as in our cities and countryside: in the hope that the deeper dimensions of making might emerge again.

So, I feel as if we are somewhat circling the same break or rift! If you are at all intrigued by this I could direct you to some writing about this topic that emerged from Trumpington Street and Scroope Terrace - there are still some voices there that speak the old language eg Dr Tao Dafour, Sofia Singler. It's just 200m from Corpus. I've belatedly realised that the architecture school should have made common cause with Divinity decades ago, as we were both excavating a similar civic poetics I think. Not too late now perhaps? Never Too Late?

You might also be more directly aware of Romano Guardini's writing on Sacred Signs - plus his laments about modernity The End of the Modern World, and Letters from Lake Como? I don't believe he and Heidegger ever met, the latter abandoned The Church in favour of some kind of pantheistic pre-Christian Hellenism perhaps.

Anyway, you're onto something I think, and there was a lot of it about after WWI. Rowan Williams gets it I think, Catherine Pickstock too.

The other voice that Dylan Thomas is echoing is Edward Thomas I think eg resonances of The Glory in parts of the reverend's poesis...?

Keep up the good work R.