This is a free taster of the more informal posts usually sent to paid subscribers, featuring miscellaneous recommendations of books, food, perfumes, etc. If you’d like to receive these regularly and access the archive, you can become a paid subscriber for £3.50 a month (the price of an overpriced coffee.)

OFFSHORE BY PENELOPE FITZGERALD

There was a week in the summer where three people independently told me to read Penelope Fitzgerald’s Offshore, which is about a community of people living on boats on the Thames, and then I met her granddaughter at a bar so I took that as a sign. It’s a beautiful, offbeat, wryly funny novel, where characters are painted through the loving and incisive observations of others. All the characters are, strictly speaking, insane, having drifted away from normal society by some process that they observe with various degrees of denial and understanding: Maurice, the male prostitute who builds a Venetian corner on his boat; Nenna, whose willingness to accept the failure of her marriage creeps in only slowly and in half-light; her two feral daughters chasing Stripey the mud-covered cat who sleeps on the chimneys, filling alternating boats with smoke every night. There’s a precise economy of prose that reminds me of Jean Rhys but with a dry, quick British wit that’s more like a Fry & Laurie sketch. There are no devastating social failures here, no irredeemable or sinister social dropouts, just a cast of odd and alive people whose inner lives and self-deceptions and attempts at understanding are painted with lightfooted generosity—people whose ‘certain failure, distressing to themselves, to be like other people, caused them to sink back, with so much else that drifted or was washed up, into the mud moorings of the great tideway.’

REPLICA BY THE FIREPLACE BY MAISON MARGIELA

Since I got a woodburner people have stopped telling me I smell like paraffin. Instead, my clothes all smell of woodsmoke, incense and a faint undertone of damp. This means that my usual perfumes no longer work (I was pairing the paraffin with gunpowder and tar scents: T-Rex by Zoologist was gorgeous—like the inside of a crystal shop—but the bottle is so offensively ugly that I held off.) My favourite perfume, Imaginary Authors’ Memoirs of a Trespasser, now feels slightly too clean. This week I found Maison Margiela’s By the Fireplace, which has the warm vanilla base of Memoirs with smokier, woodier top notes that compliment the smell of woodsmoke.

ROAST BEEF SANDWICH AT TAP SOCIAL WHITE HOUSE

For Oxford locals. I’ve been so hungry lately and this is my favourite lunch. It’s like £5.

BOOTS FROM & OTHER STORIES

I hate replacing my everyday boots and put it off as long as I can, but my old ones (pointy-toed chelsea boots from Vagabond) were letting water in and had started growing mould. I’ve been looking for knee-high ones with a narrow ankle which don’t look like wellies, which has proven impossible, but I love these from & Other Stories. I’ve got another pair of boots from them which are surprisingly comfy and have survived my tramping around riverbanks.

BODLEIAN READER CARD

If you have research interests which would justify use of the Bodleian collections (every book published in the UK and then some) you can get a reader card and use the libraries whenever you want. Huge freedom in being to use a copyright library without any reading lists or deadlines. Also warm place to sit for free.

MAXMARA AT BICESTER VILLAGE

January sales at Bicester Village are hell on earth but occasionally worth it. I went for the Agent Provocateur closing down sale (RIP) but the best find was a cashmere and silk jumper in MaxMara. It was one of the more expensive ones at £170 (down from £570—this is a version in yellow) but most of the jumpers were under £100 and obviously worth much more. If you’re shopping online sales, I recommend the Reiss sale for good quality basics—tank tops, t-shirts etc; sort price low to high.

THE CAMBRIDGE MIND: NINETY YEARS OF THE CAMBRIDGE REVIEW, 1879-1969

I found this in St Philip’s Books, a Catholic bookshop in Oxford that’s impossible to come out of empty-handed. It’s a fascinating collection, with articles by Bertrand Russell, J.M. Keynes, Quentin Skinner, Wittgenstein, G.E. Moore and T.S. Eliot. The historiography section is particularly interesting: Maitland on Lord Acton, Geoffrey Elton on Maitland, Trevelyan with a review of Herbert Butterfield’s biography of Napoleon, who ‘tore his way into the ancient fabric of the European states, and so manged the processes of historical change.’ I largely avoided learning about nineteenth-century historiography during my degree and didn’t understand what I was missing until reading this. The collection goes up to 1969—a year which occasioned an article by Raymond Williams ‘On Reading Marcuse’ and some early Plath poems (including Street Song, which I hadn’t encountered before)—and the ninety-year chronological sweep gives a useful picture of the changing shape of academic humanities, particularly in the post-war period. Chronological essay collections, generally, are good for this.

ENYS MEN BY MARK JENKIN

The Feast, last year’s Welsh-language horror by Lee Haven Jones was disappointing—it felt like an art school project and the commentary on nationalism and exploitation of natural resources was badly written and heavy-handed—but I’m much more hopeful about forthcoming Cornish folk horror Enys Men. Jenkin’s Bait was so brilliant and tackled those themes in an interesting way without falling into the same Celtic fringe cliches. I’m very bored of photography projects set in the Welsh Valleys or Glasgow that do the same washed-out depressed post-industrial working class thing, where everyone’s shot close-up in high-definition so you can see all their pores or looking miserable in a workingmen’s hall. There’s something much more unsettling and disturbing and interesting about the landscapes of Britain’s various strange insular communities which make them ideal settings for folk horror—which, as the 1973 Wicker Man showed, can be beautiful and terrifying in full saturation.

THE WRITER WHO BURNED HER OWN BOOKS

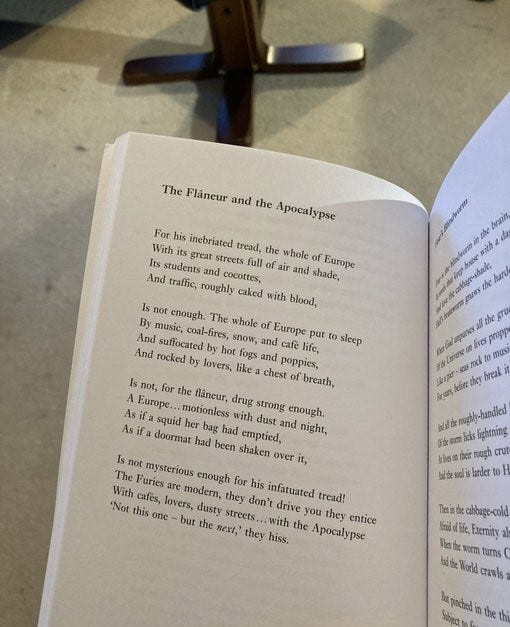

Until this article by Audrey Wollen in the New Yorker, I’d never heard of Rosemary Tonks, the poet and novelist who, after her conversion to Evangelical Christianity, ‘systematically check[ed] out her own books from libraries across England in order to burn them in her back garden’ and refused to read anything but the Bible. I’m still thinking about this part:

Accounts of her life suggest that her conflict was not with the content, necessarily, but the very concept of writing for others at all. In 1999, she noted in a private journal, “What are books? They are minds, Satan’s minds. . . . Devils gain access through the mind: printed books carry, each one, an evil mind: which enters your mind.” She was afraid of finding someone else’s thoughts left behind in her personality, like a strange scarf unearthed from the sofa cushions after a party. Books were the most acute threat to the sanctity of the bordered self. Of course, Tonks is right: that is what reading does—it places another’s mind in your own mind. It is the swiftest metaphysical delirium we have, impossible to replicate. The immensity of what reading feels like should not be discounted by its omnipresence in our daily lives. How do we distinguish between the sentences that sprout and green from our own selves, the arcane loam of the individual, and the sentences that fall and land there, alien and already bloomed?

Today, by coincidence or providence, I found a volume of her poetry in a friend’s office. I sympathise with the paranoid-magical approach to reading; books always seem to appear at the right time or to suggest themselves on the shelf when my mind is primed to be shaped by them—though I tend to think of this activity as divine rather than demonic (perhaps this is a difference between Catholic and Evangelical Christianity: a tradition always unrolling, guided by the hand of God.)

I’m sorry twitter became intolerable. People are so judgey and dismissive and disrespectful.

oxford locals rise <3 lunch is hideously expensive here