At mass last Tuesday—the feast of St Rose of Lima—the priest read an extract from her writings. As often happens, it was perfectly timed to strike a chord with me.

‘Our Lord and Saviour lifted up his voice and said with incomparable majesty: “Let all men know that grace comes after tribulation. Let them know that without the burden of afflictions it is impossible to reach the height of grace. Let them know that the gifts of grace increase as the struggles increase. Let men take care not to stray and be deceived. This is the only true stairway to paradise, and without the cross they can find no road to climb to heaven.”

When I heard these words, a strong force came upon me and seemed to place me in the middle of a street, so that I might say in a loud voice to people of every age, sex and status: “Hear, O people; hear, O nations. I am warning you about the commandment of Christ by using words that came from his own lips: We cannot obtain grace unless we suffer afflictions.

“We must heap trouble upon trouble to attain a deep participation in the divine nature, the glory of the sons of God and perfect happiness of soul.”

That same force strongly urged me to proclaim the beauty of divine grace. It pressed me so that my breath came slow and forced me to sweat and pant. I felt as if my soul could no longer be kept in the prison of the body, but that it had burst its chains and was free and alone and was going very swiftly through the whole world saying:

“If only mortals would learn how great it is to possess divine grace, how beautiful, how noble, how precious. How many riches it hides within itself, how many joys and delights! Without doubt they would devote all their care and concern to winning for themselves pains and afflictions. All men throughout the world would seek trouble, infirmities and torments, instead of good fortune, in order to attain the unfathomable treasure of grace. This is the reward and the final gain of patience. No one would complain about his cross or about troubles that may happen to him, if he would come to know the scales on which they are weighed when they are distributed to men.”

I wrote about Simone Weil’s understanding of affliction earlier this month. For Weil, affliction carried the highest risk—the possibility of destroying at least part of the soul, degrading the essence of a human person until they became a thing, a living corpse—but it was also civilisation’s only hope. It was only by experiencing the weight of affliction and transcending its terrible gravity that a soul had any hope of growing in moral character. Living through the cataclysms of the 1930s and 40s, the possibility that humanity might rediscover those ancient virtues described in the Iliad, the Gospels and Platonic dialogues—courage, fidelity, friendship, integrity, the willingness to sacrifice one’s own life—was for Weil the only way out.

This week I’ve been reading The Visionaries by Wolfram Eilenberger, a group biography of Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Ayn Rand and Simone Weil, tracing their intellectual journeys against the backdrop of the self-immolation of Europe (it’s the same genre as Metaphysical Animals, which I also loved — biography that doubles as intellectual history).

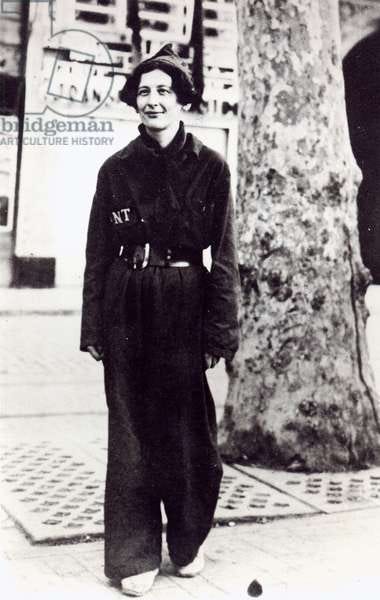

Weil, more than the others, was able to look into the depths to which the human soul was capable of sinking—in the cold, mechanical cruelty of the Holocaust as in the industrialised exploitation of the proletariat—and script a plan for reconstruction. Like St Rose of Lima (known for the silver crown ringed with spikes which dug deeply into her skull—rendered in iconography as a crown of roses), Weil undertook, even before her conversion to Christianity, extreme mortifications of the flesh and acts of self-renunciation. As a schoolteacher and trade unionist she took from her wages what an unemployed worker made on state relief and donated the rest to her comrades (a practice which Simone de Beauvoir recorded in her diaries, describing the threat she felt in being confronted by a person of much greater integrity than herself). Weil’s refusal, during the war, to eat more than was given to French soldiers at the front contributed to her death. She sought out affliction. She enrolled in factory work and signed up to fight with the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War, being an active liability in both roles (she never met minimum production targets at the factory and was denied a rifle in Spain before being sent home with severe burns from stepping into a pot of cooking oil.)

It’s easy to dismiss these experiments as a naive romanticisation of suffering—LARPing as working class when her background guaranteed that such circumstances were always temporary. There’s another depth of affliction that comes with entrapment—absolute powerlessness before an enemy or an institution far more powerful than yourself (The Visionaries does a good job of communicating just how common this experience was to the exiles and refugees flooding west, among them Arendt.) It’s the inescapability of poverty which makes it such a battering ram to the soul. She could be accused, like St Rose of Lima or Lana del Rey, of romanticising suffering without really understanding the condition of someone trapped by it. But I think it’s more that Weil thought with her entire being. Her intellectual experiments required commiting her entire lifestyle to a proposition to explore whether there was any truth to it. Her thought was fundamentally experiential, governed above all by her encounters with supernatural grace. She reached the conclusion that it was only this willingness to risk powerlessness—and thereby open oneself up to grace—which could allow a person or a civilisation to be saved.

I’ve found reading Weil so generative because I have a similar methodology. I struggle to consider an idea in a purely rational or abstract frame (Weil and Rand are about as diametrically opposed as any two thinkers could be). I have to inhabit it and understand it from the inside out. I have to act like I believe it to appreciate why someone might and thereby understand its relative merits and drawbacks (maybe this is poor theory of mind more than anything else). People have told me that it’s hard to tell what I believe; typically, I don’t know what I believe, at least not before I’ve spent a few months trying it out. My process of thinking and testing ideas involves my whole life, personality, interests, pastimes, the people I speak to and the places I go. I’ve gone back again and again to a (probably doomed) relationship to test ideas about love, commitment and sacrifice. I went to Naples to test ideas about risk. Throughout a relationship with a tutor, I wrote extensive diaries, aware that I had a rare opportunity to learn about power and desire. Lines of inquiry take on a providential aspect in this atmosphere. References present themselves. I suspect that reading lists and bestseller lists have caused people to neglect this capacity to trust their instincts. Knowledge then becomes an entirely individual pursuit—product of a single mind, a lone genius, rather than a collaborative effort informed by relationship, chance and God. The scriptorium replaced by the office.

This approach to knowledge has allowed me to endure painful experiences with a degree of curiosity which guards against self-pity. Even in the coldest weeks of the winter, when I woke up in the middle of the night in acute physical pain, the condensation having turned to ice on the inside of the windows, I didn’t entirely resent the experience because I wanted to see what it could teach me. I want to know what things look like from the inside, what they do to the psyche and the soul. I think this is why Weil lived like she did. For her there was no barrier between intelligence and soul. Both were implicated in affliction. Both had to be engaged in attempts to understand the grave crisis facing twentieth-century society. For Weil, intellectual and material risk went hand in hand.

Affliction destroys intelligence and renders the afflicted mute. But neither can someone who has not experienced affliction hope to describe, understand or begin to solve it. Going through the pain and managing to survive, soul intact, is necessary not only for the saint but also for the theorist, the educator, any person who hopes to be of any help. Weil was dismissive of Marxists who stuck to theory when evidence of suffering under the Stalinist regime mounted before them. Those who were unwilling to carry their souls into the very heart of the question couldn’t hope to land upon the truth. It would be crucial, then, for intellectual life to involve a high degree of risk.

In The Need for Roots, she writes:

‘Risk is an essential need of the soul. The absence of risk produces a type of boredom which paralyses in a different way from fear, but almost as much. Moreover, there are certain situations which, involving as they do a diffused anguish without any clearly defined risk, spread the two kinds of disease at once.

Risk is a form of danger which provokes a deliberate reaction; that is to say, it doesn’t go beyond the soul’s resources to the point of crushing the soul beneath a load of fear. In some cases, there is a gambling aspect to it; in others, where some definite obligation forces a man to face it, it represents the finest possible stimulant.

The protection of mankind from fear and terror doesn’t imply the abolition of risk; it implies, on the contrary, the permanent presence of a certain amount of risk in all aspects of social life; for the absence of risk weakens courage to the point of leaving the soul, if the need should arise, without the slightest inner protection against fear. All that is wanted is for risk to offer itself under conditions that it is not transformed into a sensation of fatality.’

The balance is very difficult. The average lifespan of thinkers like this—mystics, essentially—tends to be short. Output in the last period of life tends to be rapid, outpacing anything before, pouring out as if divinely inspired. Think of Plath’s Ariel.

‘In the history of humanity, there can have been few individuals more productive than was the philosophical Resistance fighter Simone Weil during only four months in that London winter of 1943: she wrote treatises on constitutional and revolutionary theory and on a political new order for Europe, and one investigation of the epistemological roots of Marxism, and another of the function of political parties in a democracy. She translated parts of the Upanishads from Sanskrit into French, and wrote essays on the religious history of Greece and India, and on the theory of the sacraments and the sacredness of the individual in Christianity and, under the title The Need for Roots, a 300-page re-design of the cultural existence of humanity in the modern age.’ — Eilenberger, p. 14.

In Judaism and Modernity, Gillian Rose presents the angelus dubiosus as an icon of what she calls speculative reason. The ‘dubious angel’ is another angel in the Paul Klee series from which Walter Benjamin took the famous angel of history, the angelus novus. The dubious angel is Rose’s guardian through a philosophical method which, as she communicates so well in Love’s Work, involves her entire life, open always to challenge, failure, relationship, learning—open, ultimately, to risk:

But here is the dubious angel – hybrid of hubris and humility – who makes mistakes, for whom things go wrong, who constantly discovers its own faults and failings, yet who still persists in the pain of staking itself, with the courage to initiate action and the commitment to go on and on, learning from those mistakes and risking new ventures. The dubious angel constantly changes its self-identity and its relation to others. Yet it appears commonplace, pedestrian, bulky and grounded – even though, mirabile dictu, there are no grounds and no ground.

This time last year I wrote happily about sailing away from civilisation, becoming feral, abandoning society and all its constraints, etc. For a while I nursed a genuine hatred of the infrastructure of normal, domesticated human life. I said things like ‘indoor plumbing will enslave you.’ All these things, like central heating and the national grid which pumped energy into your house without you having any idea how it got there or any role in making it happen, all of these things made people servile and complacent, slaves of energy companies paying whatever ridiculously inflated bill came through the post. On the other hand, if you have to get your own wood and chop it and light a fire, you quickly learn the cost of complacency. You’re forced to take direct responsibility for your needs or you freeze. This was a good lesson. I’ve learnt many things about the value of risk, the strength of communities where resources are scarce and interdependence necessary, and the value of suffering as a training school for both surrender and moral responsibility.

However, I’ve also gained more respect for ‘civilisation’ as a concept—as in, the edifice built up around human nature that moulds it into something capable of higher things like morality and rationality. If the cold is hammering at you every night with blunt force it becomes difficult to think of anything except your immediate needs and how to meet them at any cost. The stretch of the river where my boat is moored, because it’s outside the jurisdiction of the Environment Agency and therefore exempt from things like mooring fees and boat safety certificates, attracts mostly social dropouts of various types. Living in this way, in very serious material poverty and outside the usual bounds of the law, inflicts spiritual damage. Watching this happen within my own psyche, played out in my emotional register and my social behaviour, has given me an appreciation, for the first time, of concepts like ‘civic duty’.

I think this is something like the shift in Augustine’s thought—from acknowledging, in his early career, the enslavement of the will to sin and the absolute dependence on grace, to coming to place more emphasis on disciplina and the role of social institutions in restraining the worst impulses of the fallen will. It comes alongside an acknowledgement that not all can be saved. The road is narrow but the burden is light. Not everyone who follows the path to sanctity will make it; some, unable to fully place their lives in the hands of God, will be eaten up by their lower natures. If grace can’t save everyone, then coercion is necessary to prevent social and political disaster.

This paradox sits at the heart of Weil’s work, which veers often into authoritarianism even as she condemns the totalitarian regimes which formed the backdrop to her thought. Both Augustine and Weil wrote against war-torn landscapes and saw how easily civilisation could give way to barbarism. Both were aware of the depths to which a human being could sink; both had loyalties not only to the City of God but to the people in front of them. A theology which gives preeminence to supernatural grace—and which thereby makes necessary a high degree of risk—is usually accompanied by a political theory which seeks to alleviate risk, whether to guide people towards grace or to limit the damage caused by those who refuse it. Coercion seems a small price to pay when the threat to the soul is so great.

In late antiquity, the end of this coercion was the salvation of the soul. In modernity its aims are much more limited: safety and production. A person matters not because of the dignity of each individually created soul but because of the instrumentalisation of their productive capacity and their ‘human rights’, which are claims of entitlement without teleology. A secularised universalism believes in salvation for none and maximum utility for all. Risk is minimised through state institutions designed for safeguarding (this, rather than education, is the principal purpose of schools.) In the absence of any framework for talking about souls, salvation, the high drama of human life with its great risks and rewards, inner lives and relationships are kept within a safe middle zone, the bounds of which are policed zealously. The pop-language of toxicity, abuse, trauma and healing is, I think, a consequence of this. There is a superficial insistence on protecting a person from anything that may destabilise them. Beneath this framework is a barely-acknowledged sense of real danger. A soul can be badly mangled without much effort. We go to great lengths not to think about this.

The only ethical life risks living unethically. It accepts the risk that the very faculties that allow moral and rational life may be corrupted. The Christian entering the gladatorial arena could, at the last moment, be consumed by the terror of death and lash out in wild panic, killing her persecutors. It’s only by risking this possibility and enduring in faith until the end that she becomes a martyr.

Wonderful, articulate essay that came just at the right time (for me).

I was thinking abt something similar yesterday. I have a fantasy where I live in a glass house overlooking somewhere beautiful, like the ocean. and no one can enter the house unless they're "safe" and "good" and won't hurt me. in the glass house, all my defenses are washed away and I can relax and surrender. I have no fear and I don't have to fear that I'll ever be hurt or in danger.

but the paradox is that, in being free to relax and surrender, my natural defenses will loosen and eventually become obsolete. so then, in actuality, I'm completely penetrable and not protected from anyone or anything at all.

risk, uncertainty, and the possibility of danger are what help us build our necessary survival skills, develop our will, and build our moral propensity to endure hardship.

thank you for sharing❤️

I am disgrac'd, impeach'd, and baffled here,

Pierc'd to the soul with slander's venom'd

sреаг. The which no balm can cure but his

heart-blood which breathed this poison.

---

It takes a devil's barb, a venom'd spear, to bring new life, a flow of blood into

a dead heart.