martyrdom, history and apocalypse

on early medieval England, Alastair MacIntyre and martyrdom as virtue

Wulfstan’s Sermon of the Wolf to the English, written just after the dawn of the second millennium, begins with a cool, urgent imperative:

‘Realise what is true: this world is in haste and the end approaches. And therefore in the world things go from bad to worse, and so it must of necessity deteriorate greatly on account of people’s sins before the coming of the Antichrist, and indeed it will then be terrible far and wide throughout the world.’1

Written in a period of particular crisis and instability (the resurgence of Danish raids, the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1012, Cnut’s invasion of England in 1016, etc), Wulfstan’s homilies presented a bleak vision. In his Sermon of the Wolf, Wulfstan listed a catalogue of sins: religious houses stripped of their lands and privileges, widows forced into marriage, the poor sold into slavery, ‘devastation and famine, burning and bloodshed in every district again and again; and stealing, killing, sedition and pestilence, murrain and disease, malice and hate and spoilation by robbers.’ As Bishop of London and then as Archbishop of York and Bishop of Worcester, holding these latter sees in plurality until 1016, Wulfstan was one of the most influential figures in the realm. As an advisor to successive kings, he drafted the law codes of both Æthelred the Unready and Cnut; in these, he called the English people to reform with apocalyptic urgency, seeing ‘his law-making in part as preparation for Endtime.’2

Reform and apocalypse were not antithetical to the early medieval mind. If the end was nigh, the moral reform of the nation and its constituent souls was the most immediate priority for a preacher. In another of his eschatological homilies, Wulfstan draws a parallel between suffering on earth and a postmortem purgatorial state (the doctrine of purgatory, as such, would not be defined for another century): ‘Those who have been dead for a hundred years or even longer may now be well cleansed. We may need to suffer more harshly, if we must be clean when the judgment comes; we do not now have the time that those who were before us had.’3 Christ had spoken of the Great Tribulation awaiting his followers at the end of time—‘They will hand you over to be tortured and will put you to death and you will be hated by all nations because of my name... But anyone who endures to the end will be saved’ (Matt. 23:9-13). Wulfstan looked at his society and saw it in the midst of those times: ‘Now Satan’s bonds are very loose, and the Antichrist’s time is well at hand.’4 The faithful should not expect to be delivered from this state. Wulfstan’s reformist agenda, rather than an attempt to appease God and save England from its viking troubles, was a means of perfecting souls and preparing for the Last Judgement (though, of course, deliverance also has an eschatological dimension). As history barelled towards apocalypse, so trials would increase in inverse proportion to the time remaining. During this period of intense suffering, the faithful would be ‘quickly purified and cleansed of sin through the great persecution and through the martyrdom that they will then suffer.’5

The heroic value of martyrdom is reflected in Old English poetry. The Battle of Maldon, recounting the doomed bravery of its warriors, depicts defeat in battle not as failure but as a kind of virtue: ‘He will always regret it, / he who thinks to turn away from this war-play. / I am old in life—I don’t wish to wander away, / but I’m going to lie down by the side of my lord, / beside these beloved men.’ Hagiographic poems such as Andreas and Fates of the Apostles, meanwhile, cast martyrdom in a heroic frame; the apostles are bold and warlike, ‘not slow to the battle, to the play of shields.’6 In Andreas, Christ appears to St Andrew and says to him, ‘Is þē gūð weotod / heardum heoruswengum; scel þīn hrā dæled / wundum weorðan, wættre gelīccost / faran flōde blōd’ — ‘War is assured for you / with harsh bloody strokes your body shall / be dealt wounds, almost like water / will the gore flood out.’7 This was more than a Germanic way of making sense of sanctity, reconciling the heroic ‘secular’ with the hagiographic. This was a theology that allowed early medieval Christians to understand the trials and tribulations of their world as preparation for the world to come. The citizens of the City of God would have their political education in suffering and violent death.

When I was introduced to early medieval history as an undergraduate, the appeal lay in its strangeness and unfamiliarity—the difficulty of approaching worldviews and values so alien to the habits of modern thought. I wrote both my undergraduate and master’s theses on early medieval theologies of martyrdom and, while I understood the significance of martyrdom to a seventh-century monk or a tenth-century king, it remained at odds with my modern understanding of sanctity and virtue. I’d grown up with a politics that valued resistance, not passive acceptance of persecution. Outside its historical context, I understood martyrdom in a pejorative sense—to have a martyr complex, to be a martyr to a cause; it suggests a pathological psychology, an avoidance of responsibility or an overweening ego hidden behind helplessness. Even among Christians, martyrdom is considered a narrow path, inaccessible and therefore irrelevant to the majority.

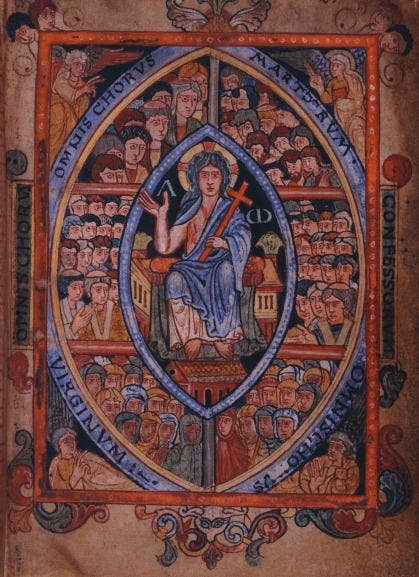

And yet, for most of Christian history, martyrdom was the highest mode of sanctity. In images of the communion of saints, martyrs occupy the highest rung; they are listed first in litanies; they receive the hundredfold reward. They remain central to the Christian faith, their bones encased in altars and adored at shrines, their passions read as examples to the faithful. Their holiness persists even if we no longer know what to do with it.

Wulfstan’s homilies, in their suggestion that periods of historical crisis and collapse should be understood through an eschatological lens, indicate an essential relationship between martyrdom, history and apocalypse—a relationship which is particularly relevant to the twenty-first century, when the dominant mood is one of hopelessness and resignation. Nobody really believes in the telos of liberal democracy or the inevitable force of historical materialism anymore. History is drained of optimism; all that lies ahead is crisis after crisis in an apocalyptic chain which we are powerless to stop or slow.

To the secular mind, apocalypse means pessimism. The end of the world is the destruction of all things and the blinking out of life. But for most of Christian history, the apocalypse was an occasion for hope. The Book of Revelation is so-named because ‘apocalypse’, in Greek, means ‘unveiling’—not the end of the world but its fulfillment, the victory over death and sin, the beginning of the world to come. Christians looked forward to redemption through cataclysmic violence: through martyrdom and apocalypse.

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ‘See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them and be their God; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away. (Rev. 21:1-4)

In the earliest Christian centuries, martyrs were the only saints. St Stephen, whose martyrdom is recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, is the first of Christ’s followers to take up his example—the first to become a saint. The next account of martyrdom is the second-century Martyrdom of Polycarp, which forms the basis for the whole genre of hagiography. After the persecution of Christians ceased in the late Roman empire, other forms of sanctity emerged: Ambrose and Jerome wrote of virginity as a kind of martyrdom while Origen and Clement of Alexandria wrote of the ‘living martyrdom’ of the ascetic. Sanctity was thus divided into categories—martyrs, confessors, virgins—but all looked back, through martyrdom, to the Cross. The whole idea of sanctity hinges on this re-enactment of Christ’s passion; all forms of sanctity are a redaction of martyrdom.

With its model in the crucixion, martyrdom necessarily possessed an eschatological dimension: death always points towards resurrection. The miracles worked by the intercession of saints, as cults grew up around their shrines and devotion attached to their bones and bits of clothing, pointed towards the continued existence of their souls with God in everlasting life. The communion of saints offered a glimpse of the New Jerusalem, bursting into history from the future.

Bede fleshed out the relationship between eschatology and martyrdom in detail, making it central to his conception of history and, in particular, to the history and future of the English Church. Taking up Augustine’s idea of the six ages of the world, Bede wrote that the sixth age, the current age, was inaugurated with the death of Abel, whom he calls ‘Christ’s first martyr.’8 The sixth age would culminate with the successive return and martyrdom of Enoch and Elijah, followed by the slaughter of all the living, making them ‘either glorious martyrs of Christ or condemned apostates.’9 Martyrdom bookends the history of man, from first to last, and its continuation through history points towards the telos of humanity—martyrdom and resurrection. If the work of the historian was to record this vera lex historiae, illuminating the passage of the world towards its redemption, then recording the passions of martyrs was an essential aspect of his task.

Between 725 and 731, therefore, Bede compiled the first example of a narrative martyrology. Previously, martyrologies had resembled calendars—dates followed by lists of names, perhaps with some brief details about location or manner of death. To this structure, Bede added narrative, focusing above all on the experience of suffering and painful death (Bede’s Martyrology is so graphic in its detail that Charles Plummer, nineteenth-century editor of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, refused to believe that a text containing such ‘ecclesiastical gloating over the physical horrors of martyrdom’ could have been authored by Bede). Despite his invention of the genre, however, Bede did not see himself as an innovator. In his Retraction on Acts, he wrote, referring to the Hieronymian Martyrology, that ‘Blessed Jerome is named in the title and the prologue of the Martyrology, although Jerome is not the author but the translator of that book, whereas Eusebius is the author,’10 indicating that he saw his own work as a restoration of a lost Eusebian martyrology to its original form.

Bede’s belief that the Hieronymian Martyrology, which he took as his main source, was a redaction of a lost Eusebian martyrology can be traced to a prefatory letter attached to manuscripts of the Hieronymian Martyrology. This letter, which Bede understood as authored by Jerome, claims that Eusebius had written a narrative martyrology detailing ‘by which judge, in which province or city, on which day, and by which suffering each obtained the palm of his perseverance.’11 This description is echoed in Bede’s description of his own Martyrology: ‘A martyrology of the festivals of the holy martyrs, in which I have diligently tried to note down all that I could find about them, not only on what day, but also by what sort of combat and under what judge they overcame the world.’12

Bede’s Martyrology, then, should be read as a counterpart to his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, both of which took up the Eusebian genres—or what Bede believed to be Eusebian genres—of narrative martyrology and ecclesiastical history, to demonstrate that the English Church was included in the universal history of salvation. To this end, evidence of continuing martyrdom was essential: in the first chapter of Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History, he sets out to relate ‘the martyrdoms undergone in our own times’, and martyrdom runs as a consistent thread throughout the history. If Bede’s Ecclesiastical History was intended to demonstrate the orthodoxy of the English Church, its membership in the universal Church and its role in salvation history, then the Martyrology must be seen as part of this project, identifying martyrdom as a necessary sign of the true Church.

Bede included one native English saint in his Martyrology: St Æthelthryth, who maintained her virginity through two marriages, the latter to King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, before securing his permission (‘at length and with difficulty’) to enter monastic life. She died as Abbess of Ely and, when her marble sarcophagus was opened sixteen years later, her body was found to be incorrupt. He does not identify as her as a martyr, but her inclusion in the Martyrology (and the exclusion of other saints whose cults claimed martyrdom—particularly those of slain kings), suggests that he granted her a special status as the heir of late antique martyrs. In his Hymn to Æthelthryth, recorded in the Ecclesiastical History, he listed her in a litany of late antique virgin martyrs: Agatha, Eulalia, Thecla, Euphemia, Agnes and Cecilia. The Hymn positions her as the contemporary equivalent to these virgin martyrs, ‘Nor lacks our age its Æthelthryth as well; / Its virgin wonderful nor lacks our age.’13 Her example proves that the incredible sanctity ‘which often happened in days gone by, as we learn from trustworthy accounts, could happen in our time too through the help of the Lord, who has promised to be with us even to the end of the age.’14

The final years of Bede’s life were concerned with reform, his latest works demonstrating a new urgency and forthrightness.15 In his Letter to Ecgbert in 734, he censured monks who were more concerned with ‘mockery and pranks, made-up stories, feasting together, and drunkenness and other wanton pursuits of a rather lax way of life’ than with imitating the saints.16 It is in this context that we should understand Æthelthryth’s inclusion in the Martyrology. As well as being a guarantee that the English people were caught up in God’s soteriological plan for humanity, Æthelthryth’s inclusion allowed her to function as an exemplar of the type of sanctity Bede sought to promote in the English Church: a sanctity which did not consider its own comfort and security but renounced the love of the world for the love of Christ. It was not virginity or asceticism which marked her out, but the particular diffuculty of her witness to Christ in circumstances which militated against her. It was through this kind of witness in adversity, Bede wrote, that Christians could imitate the martyrs ‘even in times when the Church is at peace.’17

The pastoral function of martyrs’ passions is to tell of another logic underlying the material struggle for survival and self-protection. In a society where safety was always transient, where war and plague and famine were everyday realities, martyrologies spoke of another system of values—the unbearable, impossible love that would lay down its life for another. To endure suffering was to reject the self-preservation which puts up your guard and turns neighbour against neighbour. Almost a thousand years later, Thomas Hobbes would argue that the fundamental and inalienable principle of natural law is the preservation of one’s own life. For Hobbes, the telos of all matter was perpetual motion; to will an end to that motion, to undermine one’s own survival, is a violation of nature. It follows that each man has a right to anything that might prolong his life or remove obstacles to his survival. Pre-emptive violence against a potential aggressor is rational, even necessary; humanity exists in a condition of ‘war of all against all.’ In Hobbesian metaphysics there was no force powerful enough to triumph over the impulse to survive. And yet the tradition of the martyrs stands against this, demonstrating a willingness to die for one’s faith, for deep love of God and the new world inaugurated by his death on the cross.

In a previous essay, I discussed Simone Weil’s reading of the Iliad, where the virtues of heroic society hinge on an acknowledgement of the unavoidable violence underlying all life. In After Virtue, Alastair MacIntyre makes a similar point (he cites Weil): the warriors of Homeric Greece possessed a ‘conception of the human condition as fragile and vulnerable to destiny and to death, such that to be virtuous is not to avoid vulnerability and death, but rather to accord them their due.’18 Death is bound up with friendship and fate, with courage and reliability: to trust in another person is to place your life in their hands. The bonds of friendship, sealed by honour, are valuable because they involve real, material risk. ‘To be courageous is to be someone on whom reliance can be placed’19 — courage is a virtue because it means that you will face death rather than betray an obligation to a friend. Society—moral society—therefore develops from a rejection of Hobbesian self-preservation. Even the most basic bonds of friendship demand a willingness to sacrifice oneself or endure suffering for another.

MacIntyre argues that this kind of virtue relies on a fixed social structure: ‘morality and social structure are in fact one and the same in heroic society.’ What a man ought to do depends on the telos of his role in society: a role which follows a narrative in which he may succeed or fail, where each man is cognisant of what he owes and what he is owed by others. The anti-egalitarian thread underlying MacIntyre’s account of virtue has inspired Rod Dreher and other postliberals, for whom virtue is recoverable only with a return to traditional social hierarchies (or, in some formulations, to absolute monarchy and an anachronistic vision of feudalism). In The Benedict Option, Dreher calls on faithful Christians to ‘take the Benedictine wisdom out of the monastery and apply it to the challenges of worldly life in the twenty-first century.’ The suggestion that monastic ‘wisdom’ (or the more nebulous spirituality) can be detached from the monastery is, ironically, a particularly liberal habit—shared by the post-Vatican II new monastic movement which offers a set of virtues and habits detached from their material, institutional context.

But to take monasticism out of the monastery is to miss the point: the structure of the monastery, in proclaiming a radically new, horizontal model of social relationships, is essential to its form of life. In rejecting the pater familias of ancient Rome in favour of a community of brothers or sisters, rejecting the reproductive hierarchy of the family in favour of chastity, the monastery is a challenge to all other forms of social life. In sacrificing the exclusivity of monogamous, conjugal love, the postulant offers their gift of love to be shared out in community—a community committed to spending its earthly life together in brotherhood or sisterhood. The desert beginnings of monasticism, where holy men and women rejected the city, the polis, the structure of life in society, remained present even in its cenobitic form.

For Augustine, the monastery was a prefiguring of the heavenly city. The monastic life was the rhythm of the communion of saints, where power and necessity are replaced by the bonds of mutual love. In a study of Augustine’s political thought, R.A. Markus writes that ‘the monastery, far from providing the model for other societies, defined the permanent challenge to all other forms of social existence.’20 It stood against the libido dominandi which, as a result of man’s fallen nature and enslavement to sin, characterised all other forms of social life. For Augustine, there could be no ‘Benedict option’ for lay Christians, no Christian empire or state. In this world, all social life would be marred by the consequences of the fall. Markus writes: ‘in so far as one could speak of any society possessing any quality of sacredness, one could do so only in virtue of its eschatological orientation.’21 A perfect Christian society, the City of God, would only be realised in the world to come.

And yet, in the monastic life, something of the world to come could be glimpsed. In the tradition of inaugurated eschatology, the world to come is both now and not yet. By his crucifixion and resurrection, Christ had declared the beginning of the new creation, where death has no dominion, where the impulses of our fallen state—to survival, self-preservation, domination over others—are washed away. The monastic life, in its vows of celibacy, poverty and obedience, prefigure this new ordering of the world. In rejecting family and reproduction, religious brothers and sisters announced the end of this world and the beginning of the next, where community was formed not by nature but by the free gift of love to all members of the body of Christ. By submitting the individual will to that of the community, the monastic life denied the libido dominandi which would cleave to singular self-preservation before the common good. As Markus, himself a former Dominican, wrote, ‘all duties in such a community were transformed into works of love.’22

The monastery’s prefiguring of the heavenly society implies a form of virtue—of sanctity—which is not tied to social position. As St Paul writes of the parousia, ‘then the end will come, when He hands over the kingdom to God the Father after He has destroyed all dominion, authority, and power.’23 Christ’s Kingdom is not of this world, nor does it emulate familiar social relations, all of which are marred by the Fall. Christ’s kingship is not rulership as we know it: he emptied himself, taking the form of a servant. ‘And everyone who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or fields, for my name’s sake, will receive a hundredfold, and will inherit eternal life.’24 It is in the context of the eschatological destruction of all power, domination and hierarchy that we should read St Paul’s radical declaration: ‘there is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.’25

MacIntyre’s argument that the virtuous life relies on narrative is, I think, correct, but his literary sources are pre-Christian or secular: the Homeric epic or the Icelandic saga. He neglects hagiography, where the life of virtue is made visible in a narrative shorn of social position. St Perpetua, in her prison diary, describes her father begging her to recant her Christianity:

While we were still under arrest (she said) my father out of love for me was trying to persuade me and shake my resolution. ‘Father,’ said I, ‘do you see this vase here, for example, or water pot or whatever?’ ‘Yes, I do’, said he. And I told him: ‘Could it be called by any other name than what it is?’ And he said: ‘No.’ ‘Well, so too I cannot be called anything other than what I am, a Christian.’ At this my father was so angered by the word ‘Christian’ that he moved towards me as though he would pluck my eyes out. But he left it at that and departed, vanquished along with his diabolical arguments.26

Perpetua’s rejection of her father’s legal authority is unusually forthright and striking, but the rejection of family ties is a commonplace of late antique hagiography. The sacrifice of the martyr is not the sacrifice of the warrior for his fellow soldier, or of mother for child, but the sacrifice of self in witness to a higher truth. Martyrdom is antisocial in a temporal sense, a betrayal of kin and community; it has no social function, it doesn’t make sense. But its betrayal of earthly community is a commitment to the communion of saints, the mystical body of Christ, the witness to a family united by spiritual rather than biological or political ties. ‘Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life.’27

The narrative of hagiography is left to us as a model of the holy life. It may take the form of a martyr’s passion, comprising only the details of their final days in imprisonment and execution, or as acta, the lives of the holy confessors and virgins whose whole lives demonstrate sacrificial witness to Christ. The narrative of a single holy life is a microcosm of salvation history, a witness to the future. The unique value of saints’ lives is in testifying to a way of life and a way of loving that is profoundly counter-cultural, almost impossible in their rejection of all the familiar logics of our society. Their presence tells us that another world is possible: a world in which death and all its consequences have been defeated, and where self-preservation is overcome by the free and fearless gift of our lives.

D. Whitelock, English Historical Documents, c. 500-1042 (London, 1995), p. 997.

L. Roach, ‘Apocalypse and Atonement in the Politics of Æthelredian England’, English Studies, 95/7 (2014), pp. 733-757.

Wulfstan, De Temporibus Antichristi, trans. J.T. Lionarons [https://archive.ph/8LBa].

Wulfstan, Secundum Marcum, trans. J.T. Lionarons [https://archive.ph/x8Zu].

Wulfstan, De Temporibus Antichristi.

Andreas and the Fates of the Apostles, ed. K.R. Brooks (Oxford, 1961), p. 58); tr. R.E. Bjork, The Old English Poems of Cynewulf (Massachusetts, 2013), p. 135

Andreas: An Edition, ed. R. North & M. Bintley (Liverpool, 2016), pp. 168-9

Bede, De Temporum Ratione Liber, ed. C.W. Jones, CCSL, 123B (Turnhout, 1977), p. 537.

Bede, De Temporum Ratione Liber, ed. C.W. Jones, CCSL, 123B (Turnhout, 1977), p. 538; trans. F. Wallis, The Reckoning of Time (Liverpool, 1999), p. 242.

Bede, Retractatio in Actus Apostolorum, ed. M.L.W. Laistner, CCSL, 121 (Turnhout, 1983), p. 106-7. The translation here is my own.

Martyrologium Hieronymianum, ed. H. Delehaye and H. Quentin, AASS, Nov. II, Pars II 21 (Brussels, 1931), p. 1; trans. F. Lifshitz, ‘Appendix 2: English Translation of the Prefatory Letters’, The Name of the Saint: The Martyrology of Jerome and Access to the Sacred in Francia, 627-827 (Notre Dame, 2006). For a full explanation of this argument, which involves a lot of very dry work on manuscript transmission, you’re welcome to email me for a copy of my thesis.

Bede, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, ed. and trans. B. Colgrave and 14 R.A.B. Mynors (Oxford, 1969), pp. 570-571.

Bede, Ecclesiastical History, p. 398-9.

Bede, Ecclesiastical History, pp. 392-3.

For this reading of Bede’s later works, particularly his commentary on Ezra and Nehemiah, see S. D. DeGregorio, ‘Visions of Reform: Bede's Later Writings in Context’, in P.N. Darby & F. Wallis, eds, Bede and the Future (Burlington, 2014).

Bede, Epistola Bede ad Ecgbertum Episcopum, ed. and trans. Christopher Grocock and I.N. Wood, Abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow (Oxford, 2013), pp. 128-9.

Bede, In Epistulas Septem Catholicas, ed. D. Hurst, CCSL, 121 (Turnhout, 1983), p. 252; trans. D. Hurst, Commentary on the Seven Catholic Epistles (Kalamazoo, 1985), p. 108.

A. MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theology, 3rd edition (Indiana, 2007), pp. 128-9.

Ibid., p. 123.

R.A. Markus, Saeculum: History and Society in the Theology of St Augustine (Cambridge, 1970), xvi.

Markus, p. 125.

Markus, xvi.

1 Corinthians 15:24.

Matthew 19:29.

Galatians 3:28.

https://www.ssfp.org/pdf/The_Martyrdom_of_Saints_Perpetua_and_Felicitas.pdf

Romans 6:4.